In recent decades, fuelled by lower and lower interest rates, we observe many large investors across the world have been re-allocating funds away from public markets, and into private assets – be those private equity or private credit vehicles. The theory behind this approach is that there is an ‘illiquidity premium’ to be earned by owning assets that are locked up for longer, boosting the returns of the investors relative to those who own assets that are freely traded on the open market.

Leaving aside the veracity of that conjecture – with some who have argued plausibly that, in fact, investors pay not to see the mark-to-market volatility of their portfolios [1] – one curious aspect of the private markets, as compared to public markets, is worth noting.

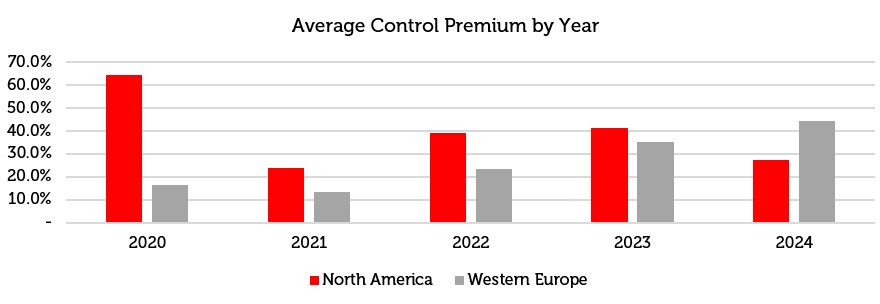

When buying companies outright, private investors necessarily need to negotiate over a single price for the entire company, a process involving numerous Board members, bankers, lawyers and accountants on all fronts, not to mention the shareholders who will be the ultimate beneficiaries of the sale proceeds. In that process, it is common for bidders to offer a “control premium”, an excess of the current market price of the company that convinces shareholders to sell, and ostensibly represents the value to the buyer of having control of the company. These premiums can range anywhere between 10% and 100% in excess of the current market value of the company, with average premiums in the ~40% range, a figure we would view as not insubstantial.[2]

Source: Bloomberg, at 11 March 2024. 2024 control premium is year-to-date. The information show above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

By contrast, when public market investors like us want to invest in a company, we don’t consult the Board or its advisors on what price they’d like us to pay – we just go into the market and buy shares from whomever is willing to sell them to us, at the prevailing price, even if that price is so low that a Board of Directors would never dream of accepting it for the entire enterprise.

By its nature, then, buying the same previously-listed company in a private equity fund or structure will cost more than simply buying shares on the open market – increasing the hurdle of corporate performance that will be required to earn investors a good return. In this sense, we believe us public market investors have a huge advantage, with the ability to make purchases at prices which we consider often so ludicrously low that any private equity firm – when trying to pay the same price for the entire company – will be quite literally laughed out of the Boardroom.

This is more than simple conjecture: in the past two weeks, two companies held in our portfolios – Curry’s and Direct Line Group – have received unsolicited buyout offers from parties seeking to take them private, and both have (we think quite rightly) firmly rejected those offers as materially too low.

Of course, no one made any such objections or consternations to us when we bought our shares on the London Stock Exchange for those same companies at similar prices (or, dare we admit, even lower prices). It is intriguing, then, that many large institutional investors – principally large pension funds – continue to eschew public markets in favour of private markets [3], especially in markets such as the UK, where public market valuations are undemanding in our view.

Yet, as the Curry’s and Direct Line example shows, this discount is not available to private bidders at prevailing prices: Boards are well aware of the despondency embedded in their market valuation, and are not going to let their shareholders be wrestled out of their companies for unfair prices. If you are the Trustee of a pension fund investing in private markets, then, you may wish to ask your CIO if they allocate to investors paying a premium to own the same assets that we get to buy without one.

As value investors, we aim to earn a superior investment return over the long-term by paying material discounts to intrinsic business value. This opportunity, however, is effectively available only in public markets, where we can buy small pieces of companies – which is, after all, what shares truly are – from sellers on the open market, and to do so at prices that we consider as so eye watering that any self-respecting private bidder would not dare to suggest.

As Curry’s and Direct Line bidders Elliot and Ageas have learned recently, there are some potentially fantastic opportunities available in the public markets – but that these are often available only to public equity investors, and are perhaps simply too good for private bidders to access.

Sources:

[1] Richardson, S. and Palhares, D., 2018. (Il) liquidity premium in credit markets: A myth?. The Journal of Fixed Income, 28(3), pp.5-23; Cliff Asness, AQR, (https://www.aqr.com/Insights/Perspectives/The-Illiquidity-Discount)

[2] Eaton, G.W., Liu, T. and Officer, M.S., 2021. Rethinking measures of mergers & acquisitions deal premiums. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 56(3), pp.1097-1126

[3] E.g. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-12-11/investors-to-increase-allocation-to-private-credit-survey-shows, https://www.pionline.com/pension-funds/calpers-mulls-boosting-private-assets-allocation, https://www.ftadviser.com/investments/2024/02/15/half-of-advisers-to-increase-allocation-to-private-assets/, https://www.funds-europe.com/investors-bullish-about-private-capital-allocation/

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.