Are oil majors surprisingly betting that fossil fuels are here to stay?

Commentators in major news sources certainly seemed to think so following Exxon’s takeover of Pioneer Natural Resources and Chevron’s takeover of Hess Corporation – deals worth a combined $130 billion.

The Guardian suggested Exxon’s move showed confidence that fossil fuel output will not be significantly hampered in coming years. Meanwhile CNBC described the firms as “doubling down on fossil fuel energy”. (source: CNBC, 2023)

But, maybe all is not as it first appears?

Rather than a sign of denial, could it be that the mega deals are actually a sign that the US oil majors really do accept that the transition to a low carbon economy is happening, and this is their defensive play to avoid stranded assets and protect themselves as the transition accelerates?

Whilst global oil demand may continue to rise for much of this decade, the underlying drivers of demand are changing fast, and this fact is likely becoming very clear to the US majors.

The European majors started to change some years ago, driven by investor pressure and European regulation, albeit their plans still fall short of aligning with a 1.5°C world. TotalEnergies, Shell and BP are diversifying into low carbon businesses, while shifting from oil to gas, and upgrading their remaining oil reserves.

The US majors have shied away from following the European path into low carbon businesses, and look terrible on Net Zero alignment benchmarks, like the Climate Action 100+ Benchmark, by comparison.

However, it may be a mistake to interpret the recent deals as a denial on their part that the transition is happening. Rather, they are transitioning in a different way: not one designed to hasten the transition nor one to profit from low carbon energy, but one that seeks to protect their shareholders through the transition, and leaving the question of their business post-fossil fuels for future management.

When an industry is in decline, the natural response of the industry is to consolidate. Take the tobacco industry as an example, the writing was on the wall for a decline in smoking following the lawsuits of the 1990s and the increasing action taken by governments and international bodies to combat the habit. Interestingly, it wasn’t until 2009 that global cigarette volumes peaked, with emerging market demand (chiefly China) offsetting developed world declines.

The tobacco industry is now dominated by three major global players (ignoring CNTC as domestically focused): Altria, Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco (BAT), and two lesser players: Imperial Brands and Japan Tobacco. Names such as Reynolds (BATS), Gallaher (JT), Swedish Match (PM), Lorillard (Reynolds/BATS), Rothmans (BATS) and Reemtsma (IB) have disappeared.

This consolidation reflected the weakness of the industry, not its strength. It reflected the need to cut costs and find synergies to remain profitable as volumes declined. It reflected the fact that regulation and a change in consumer behaviour had fundamentally changed the industry forever.

The analogy between fossil fuels and tobacco is not perfect, but it is instructive.

Looking at the recent deals – Exxon acquiring Pioneer and Chevron acquiring Hess – some notable similarities stand out between those two deals. Both transactions have expectations of c. $1 billion of annual synergies. Costs savings include savings in capital and operating expenses, general and administrative expenses, taxes, and improved resource recovery. As CEO of Chevron said, “We’ve got too many CEOs per BOE [Barrel of Oil Equivalent] when you look across the whole spectrum.”

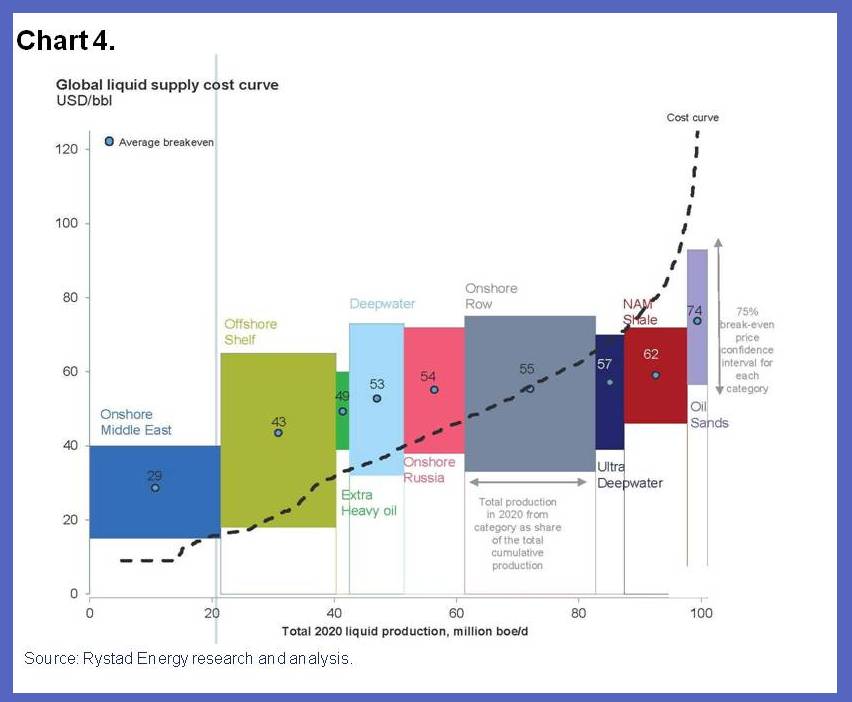

While synergies are a normal part of any transaction, there is also a focus on upgrading portfolios. Upgrading means buying assets that offer low cost barrels and selling assets that have high cost barrels. Exxon, by buying Pioneer, gets these lower cost barrels (c. $35 per barrel) in the Permian Basin, and this is further improved by combining with Exxon’s existing presence in the area.

Meanwhile, Chevron, by adding Hess’s asset in Guyana, are gaining exposure to some of the most competitive oil assets in the world (Rystad Energy estimate average breakeven cost per barrel of $28 and a location that Exxon is already very active.

Source: IMF/Rystad Energy, December 2014. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

Exxon gives another important hint as to their thinking: “By 2027, short-cycle barrels will comprise more than 40% of the total upstream volumes, positioning the company to more quickly respond to demand changes and increase capture of price and volume upside”.

Short cycle means having the flexibility to get the oil out of the ground faster and to stop investing if demand falls away; they may talk about ‘upside’, but the flexibility also protects against a drop in demand and price. Exxon intends to exploit Pioneer’s assets faster than Pioneer had planned; , this is an admission that while oil demand may rise into the end of the decade, the company is preparing for a very different oil demand outlook in the 2030s.

One other very important observation on these deals is that both are being done with paper i.e. Pioneer and Hess shareholders get shares of Exxon and Chevron. The acquiring companies are not willing to use their balance sheets to fund these transactions, which, given that both companies are virtually debt free, was not out of the question.

In summary, neither company is willing to spend more money on exploring for new oil and gas assets, nor willing to spend cash to acquire oil and gas assets, but both companies are focused on making their portfolios more flexible, low cost and resilient in the face of a transition that is undoubtedly underway.

For all of us worried about climate change, it may not sound that much to shout about, but for me it is a very strong signal that real progress is being made. I believe a low carbon future is on its way.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.