As we approach the vernal equinox, two related developments have piqued the interest of both the dedicated Japan-watcher and the more detached global asset allocator.

In a speech in Nara on February 8th, the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ’s) Deputy Governor, Shinichi Uchida, discussed the possible re-emergence of a desirable wage-price spiral and suggested that the Bank might raise the policy rate from slightly below zero to 0.1%. Rate watchers, accustomed to the ambiguous utterances of Governor Ueda, seem to have interpreted this as clear evidence that the Bank would finally raise rates into positive territory and start a possible march down the path of policy ‘normalisation’.

While both the Governor and his deputy have stressed that any policy shift would be likely to be glacially gradual – and we don’t see market participants expecting anything more dramatic – this looks to have been interpreted as a sea-change, and markets started to respond accordingly.

The Yen, which for a long time has been anchored at the $=¥150 level, has risen in the week ending Friday, 15 March.[1]

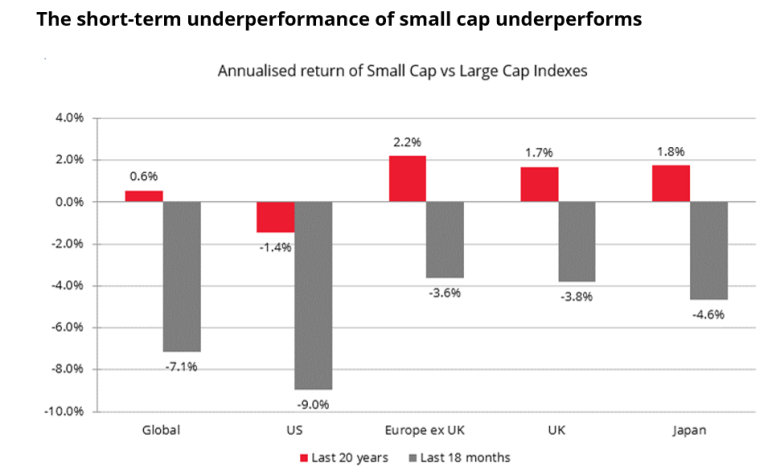

Given the extremely narrow focus of foreign buying into large-cap exporter and weak Yen beneficiaries over the past 18 months, inevitably questions are being raised as to whether we are close to a turning point in the market. Following 20 years of small-mid cap outperformance in Japan, the recent drag (see chart) looks to be somewhat anomalous and perhaps related to foreign investors seemingly still not displaying deep interest in the fundamentals of most companies.

Passive funds account for more than 90% of stock buying by overseas investors since the start of 2024*.[2]

Source: Topix 100 vs Topix Small Index, Bloomberg, 06 February 2024. Past performance is not a guide to future results.

Secondly, while BOJ officials ponder their next moves, and market pundits dissect every possible detail, this year’s shuntō (‘spring offensive’) wage round has been producing some numbers we believe suggest corporate Japan may finally be assisting efforts to regain the Bank’s targeted underlying inflation rate of 2%.

ANA Holdings, Honda and Nippon Steel have all granted their largest wage increases for over 30 years, while large companies in general have raised wages by 4.0%, up from 3.6% last year.[3] Even Toyota – which has a less than generous reputation – came through with its largest increase on record.[4]

So, is this the beginning of the longed-for wage-price spiral? Well, a bit – maybe – and, maybe, just enough.

An important point to note is that Japanese companies and unions typically express their headline wage increases in numbers which include the so-called ‘fixed period increment’ – the annual increases granted automatically in line with the employee’s seniority/tenure. This creates a gently upward sloping age-wage curve for the individual employee, whilst doing nothing to the company’s overall wage bill or, in aggregate, to liquidity in the economy at large. It is the lower, so-called “base-up” number, that matters. So, around 2% can usually be deducted from the advertised headline numbers.

Further, in ‘normal’ times gone by, there was a routinely (very) high correlation between the relative tightness of the labour market, as indicated by the ratio of job vacancies to applicants, and the general rate of shuntō increases. We’ve observed this relationship brake down dramatically over the past 20 years or so and the increases being posted this year only go some small way to redress the balance in the currently extremely tight jobs market.[5]

Finally, while the wage settlements in the large companies may have some influence on the mid- and small-cap outfits further down the food chain, which employ around 70% of all workers in Japan, the dynamics in those segments are often very different, and for the most part, haven’t been buoyed by the recent effects of Yen weakness.[6]

Despite the above points tempering some of the headline enthusiasm around wage inflation finally coming to Japan, any move higher in wages is of course, “a good thing”. How these socio-economic realities combine with a more welcoming environment for Engagement, the ongoing Corporate Governance reform, BoJ rhetoric and any concomitant move in the Yen remains to be seen. Most importantly for the active equity investor, how these factors drive the all-important marginal buyers of Mrs Watanabe and foreigners, will set the direction of the Japanese equity market in the next couple of years.[7]

Mrs Watanabe’s recent excursions into equities have, for the post part been into US stocks, but this could change. Japanese securities houses will no doubt be marketing the new tax-effective NISA launch with gusto, and encouraging her return to the domestic market.

Foreigners need to be convinced that the current revival is more than a flash in the pan; that the ‘lost’ decades were not entirely lost; and that Japanese companies have abiding strengths and real prospects, before a root and branch, fundamentally focused recovery in the Japanese equity market is seen.

Having been at the forefront of market interest for more than a year now, maybe the time is nigh. In any case, from any perspective the environment and mood music look to be improving in our view.

Sources:

[1] Tokyo Stock Exchange data, 15th March 2024

[2] Tokyo Stock Exchange data, 15th March 2024

[3] ANA Holdings, Honda , Nippon Steel,Toyota, Company disclosures as at 14th March 2024

[4] Financial Times, 13th March 2024

[5] Nihon Sangyo Rodo Chosa-Jo, as at 18th March 2024

[6] Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Japan, as at 18th March 2024

[7] Mrs. Watanabe is a term that gained prominence in the early 2000s, representing a stereotype associated with Japanese retail market traders.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.