Whilst I have never understood the need to write outlooks at the start of every year (why would the outlook change between 31st December and 1st January?), I thought it would be useful to provide an update on some of the themes that we have been discussing in the last eighteen months, particularly in light of some sharp price moves in the first couple of weeks of this year.

1. Inflation

Until recently, the market seems to have taken the view that inflation would be transitory and would eventually fall back to acceptable levels; this is the only way we can rationalise negative real (and in some cases negative nominal) bond yields, as well as the very high valuations of long duration assets such growth stocks. As time has gone by, however, this notion of transitory inflation has looked less plausible with even Jay Powell, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, recently saying “it’s probably a good time to retire that word (transitory) and try to explain more clearly what we mean when talking about inflation”.[1]

The following datapoints suggest that inflation is becoming a major issue and something that many investors have never had to contend with.

- Producer price inflation in Spain, Italy and Germany is now running at 33%, 27% and 19% respectively (PPI YoY%, Bloomberg 31 December 2021).

- In December 2021, US consumer price inflation was 7.0% year on year, the highest in 40 years; US producer price inflation came in at 9.6% year on year, the biggest annual gain ever (Bloomberg, 31 December 2021).

- US house prices rose by 23% in 2021 which is faster than at the peak of the sub-prime bubble (Bloomberg, 31 December 2021).

One can no longer ignore the data, inflation is clearly picking up and continued supply disruption, as well as a potential energy crisis, suggest this could be with us for some time.

2. Central bank reaction

Understandably, many investors have been conditioned to believe that central banks will always prioritise supporting asset markets with low interest rates and quantitative easing over curbing inflation because this is how they have always behaved in the last decade. The so called ‘Powell pivot’ of 2018 was perhaps one of the clearest examples of this when Jay Powell’s attempt to unwind asset purchases by $50bn a month was met with a 20% decline in the stock market and complete capitulation by the Fed. This was easier to believe during a period when inflation was under control, but this no longer seems to be the case. A central bank that takes no action to curb inflation running at the levels noted above risks losing its credibility and if this happens, inflationary expectations become embedded in both consumers and manufacturers. It was, therefore, very notable that the recent minutes of the Federal Reserve Board meeting suggested that members felt it was appropriate to take firmer steps to control inflation.

“It may become warranted to increase the federal funds rate sooner or at a faster pace than participants had earlier anticipated. Some participants also noted that it could be appropriate to begin to reduce the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet relatively soon after beginning to raise the federal funds rate. Some participants judged that a less accommodative future stance of policy would likely be warranted and that the Committee should convey a strong…“

Source: Federal Open Market Committee, as at 15th December 2021

This announcement has had a major impact. A few months ago, investors were assuming no rate rise in the US until April 2023 whereas they are now assuming four in 2022. In addition, the Fed has gone from talking about slowing down the pace of its quantitative easing programme to discussing shrinking the balance sheet which could involve selling bonds back into the market. This is a major shift. Central banks have been buying $26bn in assets every trading day since Covid began and hence added $10.5 trillion to their balance sheets between 2020-21. This year they are expected to subtract $0.6 trillion (Bloomberg, 31 December 2021).

Understandably, bond yields have moved up rapidly in reaction to this with the US ten-year yield approaching 1.8% (see chart below) and this has been accompanied by a sell-off in technology stocks with NASDAQ declining by 4.5% year to date (Bloomberg, 10 January 2022).

Source: Bloomberg, as at 10th January 2022

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part.

3. Impact on long duration assets

This change of mindset from the Federal Reserve could have implications for overvalued long duration assets and technology stocks are possibly the most egregious example of this:

- The median price to earnings ratio of the top ten largest stocks in the US is now 37x with the distinct possibility that these earnings represent peak margins which will come under pressure as input costs rise.

- The largest five companies in the U.S. trade for 46x free cash flow or 57x if you remove the cash flow benefit of stock-based compensation. Stock compensation expenses were 19% of these firms’ collective free cash flow.

- Software stocks are almost twice as expensive as they were at the peak of the TMT bubble. The median stock in the sector now trades at 18x sales.

(Bloomberg, 31 December 2021).

These sorts of valuations seem to assume that interest rates will remain low and that central banks will continue to supply the market with liquidity. As the Federal Reserve is now telling markets this is not the case, there would seem to be a lot of risk in this assumption and the implications of this are very significant.

4. Are markets starting to price in a regime change?

As we pointed out in a recent blog, Canary in the Coal Mine, investors could be forgiven for believing that markets remain very healthy if they merely looked at the large indices such as S&P 500 finishing +27% last year and NASDAQ +21% (Bloomberg, 31 December 2021). What these disguise, however, is the poor breadth of the market with four stocks (Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia and Google) generating over half of the S&P 500’s return in the final six months of the year (Bloomberg, 31 December 2021). We showed in that blog that beneath the surface things were far from healthy, for example, the Goldman Sachs non-profitable technology company index lost 28% in a month (16 November 2021 to 16 December 2021) whilst the ARK Innovation ETF had lost 40% from its peak in February 2021 (Bloomberg, 12 February 2021 to 31 December 2021). The Hang Seng tech index is down 48% (Bloomberg, 17 February 2021 to 31 December 2021), the SPDR biotech index is down 36% (Bloomberg, 08 February 2021 to 31 December 2021), bitcoin is down 31% from its high (Bloomberg, 10 November to 31 December 2021)

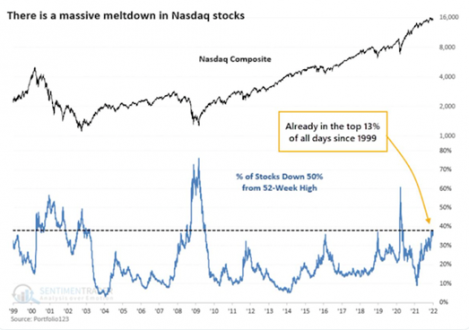

This was again highlighted in a recent article by Bloomberg[1] which pointed out that 40% of NASDAQ Composite stocks are down 50% or more from their 52-week high.

“Another way of thinking about the tech wreck: At no other point since the bursting of the dot-com bubble have so many companies fallen like this while the index itself was so close to a peak.“

Source: Portfolio 123, as at 15th January 2022

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part.

It is worth noting that this has continued in to 2022, although the sell-off seems to have widened from the more speculative parts of the market. NASDAQ is down 4.5% in absolute terms including some the larger names with even Microsoft down 7% year to date and Google down 4%. Looking at sectors, there has been a marked divergence between energy related sectors such as Exploration and Production (+10.8) and Refiners (+11%) and Application Software (-13%) (Bloomberg, 10 January 2022).

5. Overvalued and over owned

When returns in a market become narrow fund managers normally have to own the stocks driving the market in order to have any chance of beating the index. Even taking this into account, every time I read a fund profile in the newspaper, I am simply staggered about the commonality of the names which appear in the top ten. It seems that everyone must now own Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Visa, Mastercard, Paypal etc. In addition, because they are such a large part of the index, they often represent a large part of fund managers portfolios with 10% holdings in some of the biggest stocks not uncommon. Although the market still seems to favour these companies, it should be obvious that having such a large part of a portfolio allocated to such expensive stocks is not necessarily defensive – no matter how great you might think the companies are. I am also somewhat cynical of the view articulated by the owners of these stocks – that they were the perfect stocks to own in a low inflation, low interest rate environment and that they are also the perfect stocks to own in a high inflation, high interest rate environment. The performance of the Nifty Fifty stocks during the inflationary 1970’s doesn’t seem to support this thesis.

There is some evidence that the smart money is adjusting positioning. Among equity long short funds, net exposures are the least short value relative to growth in at least four years. On the quant side, value exposure has risen lately (and growth has fallen) such that net positioning between these two factors is at near highs once again.

6. Time to consider increasing exposure to value

There are numerous reasons to consider rotating to value at the moment:

- Many investors seem to be heavily exposed to growth as recent returns have been so strong and they are extrapolating them forward. This ignores the fact that a good part of these gains has come as a result of a rerating (growth stocks getting more expensive). Not only is it mathematically unlikely that growth stocks can continue to rerate forever, it is actually more likely that future returns may be negatively impacted by a derating.

- The gap in valuation between value and growth is greater now than it was in 2000. This should be an opportune time to rebalance from growth to value.

- Some of the ‘value’ parts of the market are those that traditionally benefit during periods of rising inflation with energy, mining and banks being obvious examples.

- A portfolio that mixes bonds with a variety of growth managers might look like it is diversified but it is actually a one-bet portfolio. If interest rates rise, then most of these assets are likely to suffer to varying degrees. Increasing exposure to value allows for greater diversification of risks.

We believe that continuous high inflation data has forced the central banks to finally take action before they lose what remains of their credibility and that this will have widespread implications after over a decade of loose monetary policy. Investors may be well advised to alter positioning to reflect this by reducing their exposure to growth equities and increasing exposure to value and particularly those sectors which benefit during a period of rising inflation such as energy, mining and banking.

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of RWC Partners Limited. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.

[1] New York Post November 30th 2021

[2] Number of Nasdaq Stocks Down 50% or More Is Almost at a Record By Vildana Hajric January 6th 2022

Unless otherwise stated, all opinions within this document are those of the RWC UK Value & Income team, as at 21st January 2022.