Nature matters – our individual human experience of nature is precious. Its value is immeasurable.

Framing nature as the basis for Natural Ecosystem Services concentrates our focus on the more tangible contributions nature provides the economy and society.

Ecosystem Services

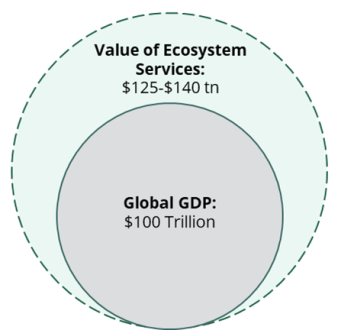

In 2019, the OECD estimated that Natural Ecosystem Services contributed $125-140 trillion of value each year [1], which it noted was more than one and a half times the size of global GDP.

Source: World Economic Forum, World Bank as at 2022. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

These Services are commonly categorised as:

Provisioning Services – resources which may be extracted from ecosystems;

Regulating Services – processes which regulate the operation of natural systems such as carbon sequestration;

Cultural Services – less quantifiable services which support the development of culture such as architecture and recreation;

Supporting Services – basic natural phenomena which underpin other services, such as photosynthesis.

For instance, primary, secondary and working forests are a crucial source of Nature Services. Accounting for more than 30% of the planet’s land[2], they offer Provisioning Services including timber, fibre, food and medicinal plants. They also provide Regulating Services including a cooling mechanism; local precipitation regulation; protection from soil erosion, landslides and floods; water filtering; and carbon sequestration.

Forests offer a range of Cultural services including leisure activities, aesthetic pleasure and psychological benefits to those who enjoy them. They also remain a source of biodiversity with potentially valuable and undiscovered genetic material.

Some Natural Services can be replaced with artificial processes. For instance, animal pollination services are worth more than $217 billion a year to the agricultural sector [3] and contribute to 35% of the world’s crop production [4]. Many pollinators are threatened by a combination of habitat loss, pathogens and pollution, raising concerns for food security.

Artificial pollination methods ranging from manual pollination to experimental micro-drone technology have some limited ability to replicate animal pollination services. In many cases it is simply not feasible to replicate Natural Ecosystem Services.

Counting the cost

It is estimated that three quarters of all land is materially altered and two thirds is suffering the cumulative effects of human activity [5]. The pace of degradation has been unprecedented – half of all forest lost in the last 10,000 years has been lost since 1900 [6].

More than half of global GDP is deemed to be highly or moderately exposed to nature [7] ; human health and wellbeing is highly dependent upon its Regulating Services which afford us access to clean air and water. Thus, the degradation of biodiversity and Ecosystem Services represent a material risk to the global economy as well as human health and wellbeing.

The World Bank estimates that “business as usual” would result in the loss of $90 – $225 billion of real GDP by 2030, depending on the extent to which natural carbon capture services are lost) [8].

Change is coming

Whilst the precise value of natural ecosystems is difficult to quantify, the cost of inaction is becoming clear. Aggravated by climate change, we are beginning to witness the impact of their degradation – declining wild food sources, the threat of crop failure, the spread of pests and disease, soil erosion and the lack of flood protection are beginning to manifest.

Evidence of the physical risk associated with inaction is stimulating policy responses. The historic Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework agreed in 2022 sets out twenty-three targets [9] to be achieved by 2030 in order that we remain on track for the long-term goals associated with the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity. Whilst policymakers grapple with the challenges associated with delivering these targets, other stakeholders are beginning to assess both their dependency and impact on nature.

We believe, these are crucial first steps towards addressing physical risk associated with dependency and transition risk associated with impact. The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) offers guidance and recommendations for the process of measurement and disclosure to enable corporates to quantify the value of nature to their business. This is a key step in the integration of nature into decision making.

What we can measure; we can address

TNFD has created the ‘LEAP’ framework to help asset owners identify key areas of risk and assess materiality through four phases:

‘Locate’ the interface with nature

‘Evaluate’ dependencies and impacts on nature

‘Assess’ nature-related risk and opportunity

‘Prepare’ to respond to and report on material issues

Given the critical influence of location on specific dependencies and impacts on nature by individual assets, the accuracy of this step is crucial to assessing the value or materiality of nature to it. It also allows us to understand where and how activities contribute to the degradation of nature and thus where we should focus efforts to limit further damage and address transition risk.

The economic case for a nature transition is increasingly clear. As we come to terms with the significance of inaction, it appears policymakers, asset owners, investors, corporates and consumers are increasingly willing to embrace the need for change. The shift is accelerating, demand for solutions is growing and funding sources are emerging to attract investment and innovation.

This represents an opportunity for the best of the solutions available now and serves as an incentive for those developing exciting solutions for the future. There is a growing body of products and services which allow the continued production of the goods and services upon which we depend but with a more limited negative impact on the natural ecosystem.

We may never be able to fully quantify the value of nature, but we are becoming aware of the cost of its loss. Progress may be slower than the science demands; but it is coming.

Sources:

[2] Forests, desertification and biodiversity – United Nations Sustainable Development

[5] Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services | IPBES secretariat

[6] Deforestation and Forest Loss – Our World in Data

Source: Redwheel. Whilst updated figures are not available, we have performed further analysis and believe that this data has not significantly changed and is reflective for 2023.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.