Part 1: Passive investing

The very essence of value investing is the search for securities which are incorrectly priced, i.e. where the market price is trading at a substantial discount to the intrinsic value of the underlying business. This will sometimes happen because the average investor is prone to behavioural biases such as extrapolation, herding and risk aversion, which might lead them to make emotional decisions such as selling a cyclical stock whose share price has declined at the low point of the economic cycle because they cannot see how things will ever get any better.

Another factor that leads to the mispricing of securities, however, is when investors are forced (or choose) to invest in a way that simply does not incorporate valuation into the decision-making process (we frequently refer to this as valuation agnostic investing). We have previously discussed one example of this which was UK pension funds reducing their exposure to UK equities from above 50% in 2000 to around 3% today[1] even during a period in which the UK equity market appeared to be one of the lowest valued equity markets in the world. As this process had been largely forced upon them by regulation, however, the low valuation of UK equities was completely irrelevant (and on the other side, the low yield and high valuation of the fixed income securities they were buying was also irrelevant). For investors like us, who use valuation as a cornerstone of their process, this behaviour is welcome as indiscriminate sellers drive share prices ever further away from intrinsic value and creates the opportunity to purchase significantly undervalued securities.

In this series, we intend to explore the subject of how the increase in the number of market participants who are valuation agnostic creates opportunities for those who focus on valuation, exploring the impact of participants such as multi-manager hedge funds, or ‘Pod shops’, and retail traders. In Part 1, however, we start with a look at how the enormous growth in passive investing – in particular, market capitalisation-weighted passive investing – has potentially increased the number of stocks that are incorrectly priced.

Definition of passive investing

Whilst passive investing can mean different things to different people, for the purposes of this paper we define it as index-tracking strategies such as those funds that hold the constituents of an index like the S&P500 exactly in line with their weightings in the index. Importantly, most of the major indices that are passively replicated are market cap-weighted, meaning that constituent companies are weighted by total market value: the larger the company, the larger the position in the index.

Passive investing has grown very significantly over the last twenty years and now accounts for over 50% of total equity investing in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETF’s) globally today [2]. Some of the largest index-tracking ETFs are now very big indeed. For instance, the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust has assets of $561.7 billion [3], the iShares Core S&P 500 ETF [3] has assets of $548.6 billion and the Vanguard 500 Index Fund (VOO) has assets of $622.1 billion [3] .

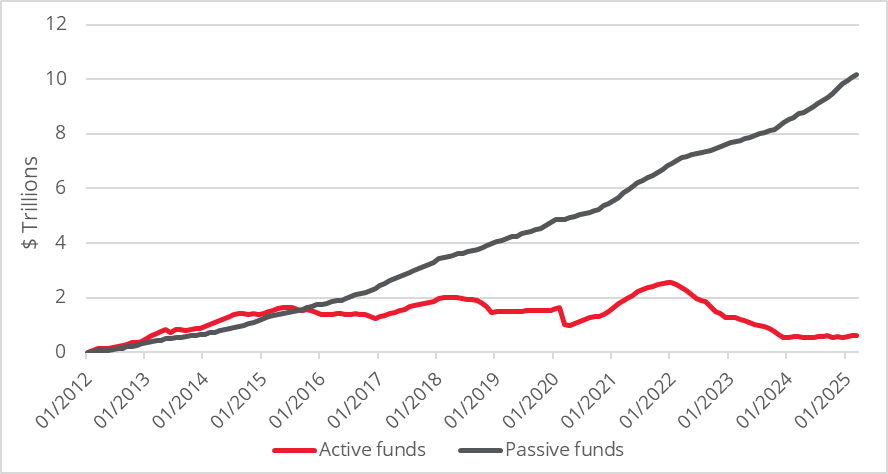

Chart 1: Passive investing makes up 43% of global equity mutual funds and ETFs

Why does it lead to mispricing of individual securities?

Put very simply, as the market share of participants who care about fundamentals and valuation is shrinking and being replaced by those who are completely indifferent to valuation, it must inevitably lead to mispricing. One of leading commentators on how passive investing is distorting markets is Mike Green, Chief Strategist and Portfolio Manager at Simplify Asset Management, a US-based ETF provider specialising in alternative strategies who sums it up as follows.

“Passive is really just the world’s simplest algorithm. Investors who analyse a company’s prospects and attempt to value businesses have been replaced by machines that are simply saying, ‘Did you give me cash? If so, then buy. Did you ask for cash? If so, then sell’.”[4]

When those with no interest in valuation crowd out those trying to figure out what a stock is worth, it eventually destroys the markets price discovery mechanism and leads to what David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital has described as ‘a broken market’:

“We are such marginal players in terms of the amount of trading that’s going on, so the price discovery from professional people who have a valuation framework, not as the dominant part of their process but as any part of their process, is much, much smaller than it used to be. And so effectively, instead of the valuation becoming the signal, the valuation people were just noise and everybody else is sort of the signal. And this is why I think we have a structurally dysfunctional market, a bit of a broken market.”[5]

How does this create a distortion?

Chart 2 below highlights the huge disparity in funds flowing into passive strategies compared to active strategies. While new money such as pension contributions can account for some this, the magnitude of the disparity suggests that considerable sums are shifting from active to passive funds.

Chart 2: Passive flows are increasing while active flows are stagnating

Active managers, particularly those who employ a value-driven approach, are typically underweight the more expensive mega cap stocks and overweight smaller but cheaper stocks. [6][7] As they receive redemptions, these stocks are sold, and the passive managers allocate a greater proportion of the money they receive to larger more expensive stocks. This impact is exacerbated by the fact that liquidity does not scale in a linear fashion with market capitalisation. For instance, Apple’s market cap is 187 times larger than Clorox but the difference in average daily traded volumes is only 35 times [8]. This means that as money flows into passive funds, not only is more money being allocated to Apple than Clorox, but each dollar will have a price impact that is greater than the differential in market cap.

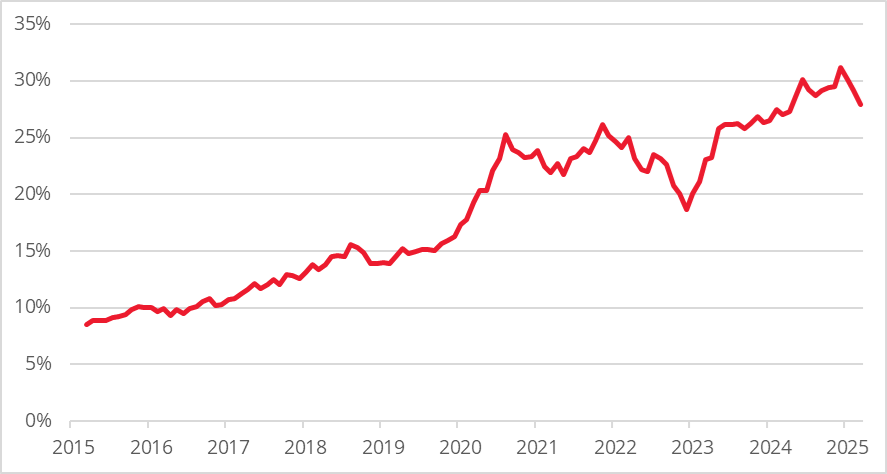

Passive has, in essence, become a giant momentum strategy. This undoubtedly has contributed to the highly distorted nature of the US stock market whereby seven very large companies have just got bigger and bigger until they eventually make up almost a third of the index. The fact that most passive funds buy more larger companies creates a reinforcing positive feedback loop: as companies get more expensive – and thus larger – the passive index buys more of them with each incremental dollar invested, further driving up the price, the company size, and the weight in the index, in a huge loop that rewards size and overvaluation.

Chart 3: Magnificent 7 as percentage of S&P 500 index

What could go wrong?

It has been pointed out above that inflows into passive funds are related to income, for instance, contributions into retirement plans, whilst outflows are a function of the overall value of savings. Passive investing works well so long as people are employed and making contributions into their 401(k)s or SIPPs. But if people started losing their jobs and ceased these contributions, the passive flows would decrease. Alternatively, the outflows from those retiring could eventually exceed the inflows from those in work and saving. Either or both would turn passive buying into passive selling and it is not clear who the natural buyers for the shares they are selling would be because the active management industry has shrunk so much. The passive algorithm would remain valuation agnostic and would just sell if asked for money regardless of how far the stock had fallen the previous day or week. Mike Green worries that this could create a situation where the market gaps down and is unable to find a floor.

The implication for value-oriented investors

Simply put, the distortions described above are driving the valuations of the large cap stocks which receive a disproportionate share of inflows significantly above their intrinsic value. Conversely, they are driving the valuations of smaller stocks being sold down by active managers significantly below their intrinsic value. Whilst it is possible to see the passive industry as a steam roller which will just flatten anything that tries to get in its way, my inclination is that this is a finite process. At some level of undervaluation, entire companies are bid for by competitors or private equity firms. Other companies use their low valuation to create enormous value by buying back their own shares. And eventually, the equal-weighted index should return to beating the market cap-weighted index and money flows out of passive and back to active.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.

Sources:

1] Portfolio-institutional.co.uk, February 2025

[2] Morningstar, March 2025

[3] Company websites, Redwheel, April 2025

[4] https://www.yesigiveafig.com/p/why-bother-being-better