Since interest rates around the world began to rise in early 2022, the banking sector has seen something of a resurgence in investors’ minds. Underpinning this is the, perhaps simplistic, notion that rising rates are great news for banks whose return on assets (loans) rise as rates rise while their primary cost of funding (deposits) remains docile. However, this note aims to set out why our framework of thinking in terms of buckets sheds a very different light on banks.

Thinking in buckets

In a probabilistic world we aim to tilt the odds in favour of our clients through our investment process which demands the rare combination of attractive yield, durability of cashflows and valuation. This combination tends to form only where there is a controversy i.e. where something is going wrong or the stock is very out of favour. There are 5 buckets of controversy where we see the market repeatedly offering up such opportunities, buckets we have become familiar with over time.

One such bucket of controversy is ‘capital intensity’. With capital intense businesses the market can regularly become bored with mundane growth, preferring more exciting higher growth alternatives. In these instances, the power of compounding at a modest rate (slightly higher than cost of capital) is underappreciated.

The enormous benefit of constantly fishing in buckets of controversy year after year is that repeating patterns emerge and a vault of lessons and analytical imperatives forms over time. When looking at the banking sector we aim to leverage the lessons from a wide range of other capital intense businesses such as utilities, airlines, mining etc.

The key lesson we have learned over the years of fishing within our capital intensity bucket is that small changes in operating conditions can undermine the payment of a dividend very rapidly. In particular, the impact of 1) financial leverage, 2) political interference, and 3) technology, social media, and globalisation, means that understanding and anticipating such operational changes is becoming extremely difficult. As our process requires us to sell stocks whose yield falls below that of the market, this sensitivity to the downside is of utmost importance to us and puts banks in a different context.

Financial Leverage

The combination of capital intensity and extremely high financial leverage within the sector means that tiny changes in non-performing loans (NPLs) can wipe out shareholders’ equity with frightening speed. With assets/equity ranging from 10-40x, equity is typically a very small component of the balance sheet. The arithmetic of such leverage is unequivocal and was eloquently evidenced during the global financial crisis. For example, it took NPLs to rise to just 1.3% of loans at Royal Bank of Scotland during the global financial crisis for the group to become the poster child for bank bailouts in the UK.

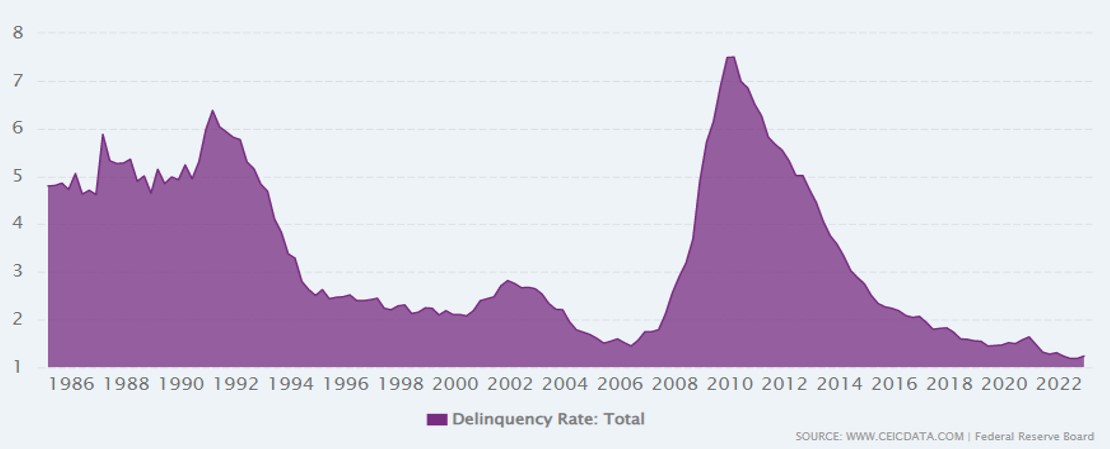

Given this sensitivity to changes in NPLs, it is important to note that NPLs, as a % of loans, throughout the banking sector are at record lows. The chart below clearly highlights the record low NPL ratios prevailing in the US banking sector, and from our own analysis, we believe this is representative of the global banking sector more generally.

United States Non Performing Loans Ratio from Mar 1985 to Dec 2022

Source:www.ceicdata.com, Federal Reserve Board, 31st January 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future results.

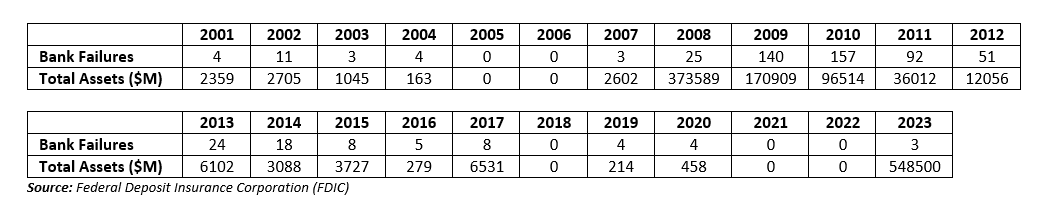

This sensitivity to even small changes in operating conditions can also be deduced from the depressing frequency of bank failures and bailouts. The following data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) shows the US experience of bank failures since 2001. Over this period, 564 US banks have failed. This represents an average of 24.5 per annum.

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), 31st May 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future results.

This litany of failure doesn’t just apply to small and medium sized banks. In 2008 and 2009, the US Treasury Department invested c$200bn in hundreds of banks through its Capital Purchase Program in a desperate effort to prop up capital. This included the illustrious names of Wells Fargo, JP Morgan, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, Bank of New York Mellon and State Street. Similarly in Europe, the major banks that required a bail-out are too numerous to mention.

Political Interference

State intervention in the form of bailouts within the banking sector has significant and multi-year implications for capital allocation and, by extension, the payment of dividends. As we saw in the years following the global financial crisis, regulation tightens, capital requirements rise and the ability to pay dividends weakens. With taxpayer money bailing out profligate banks, banks often become parastatal and political in nature. It becomes politically very difficult to allow banks to return capital to shareholders when they have been bailed out. While it is difficult to disentangle financial stress with political interference, Royal Bank of Scotland didn’t pay a dividend for 9 years post 2008. Lloyds didn’t pay a dividend for 5 years. Indeed, more widely beyond the banking sector, we clearly saw that the quid pro quo of taxpayer help during the covid pandemic was an impingement on dividend payments.

Government coercion and its influence on capital allocation can come in other forms too. Banks may be coerced into takeovers, the terms of which, are rarely favourable. Just as Lloyds were encouraged to buy struggling Halifax Bank of Scotland (HBOS) during the height of the global financial crisis of 2008/09, JP Morgan was ‘brokered’ by the US Government to acquire First Republic as it was failing in early 2023.[1] The fallout of these more recent problems in the US banking sector saw UBS being coerced into buying a failing Credit Suisse.[2]

Technology, Social Media and Globalisation

Recent problems within the US banking system represent powerful evidence that banks are becoming increasingly sensitive to operational challenges. Silicon Valley Bank failed as depositors took fright at the impact of relatively small interest rate rises (interest rates remain low by historical terms) on unrealized losses in its held-to-maturity investments in US Government bonds (hardly a major credit risk). While it took two weeks for over $17bn of deposits to flee Washington Mutual in 2008 (the largest bank failure in US history), Silicon Valley Bank lost 2.5x that in a single day in 2023. This is a stark reminder that depositor behaviour can now correlate with frightening speed in a social media-driven, viral world. And, with suitable irony, it is the banks themselves that have created the conduit for this in the form of their online banking apps and technology.

This online conduit is important because banks’ key funding source, deposits, has historically been docile and slow to demand higher rates of interest. This stability has been a direct consequence of low correlation in depositor behaviour. It remains to be seen whether this stability, and its associated low cost, can be relied upon in an online world.

This heady combination of rapidly advancing technology, social media, leverage and global interconnectedness means that the so called ‘butterfly effect’ is likely to become more powerful within the banking system. The butterfly effect relates to the notion that seemingly trivial events can ultimately result in much larger consequences i.e. they have non-linear impacts on very complex systems. Just as problems in some esoteric mortgage-backed securities in the US led to a near total collapse of the global banking system within weeks in 2008, events at Silicon Valley Bank in California helped to lead to the collapse of Credit Suisse within a few short days in early 2023. In particular, widespread fear of contagion from the collapse of SVB and the subsequent statement from Credit Suisse’s largest shareholder denying any intention of adding to its existing stake caused panic among investors who now feared a catastrophic withdrawal of capital from Credit Suisse.

Current Positioning

The sensitivity of banks’ earnings and balance sheets to changes in NPLs means that our instinct is to prefer banks at times of peak NPLs. When NPLs are near to peak, outsized returns can be made. However, a very active approach is required because dividends are often suspended or reduced at this point in the cycle.

When NPLs are near record lows, as they are currently, opportunities are scarce.

Svenska Handelsbanken is the strategy’s only bank holding. It is the nearest bank we can find to a utility which we believe is the optimal mode of behaviour for a bank.

This, we believe, is thanks to its unique corporate structure. Individual branch managers are solely responsible for all operations within their branch’s proximity and report directly to the head of the relevant regional bank. All credits must be approved by the local branch manager who ‘owns’ the credit for its entire maturity.

Performance of individual branches is monitored in terms of the cost/income ratio (including risk-weighted cost of capital), the true funding cost and actual loan losses. As a result, profitability always dominates volume, and the financial goal of the group is to have higher profitability than the average of its competitors through having more satisfied customers and lower costs (including loan losses) than its competitors. This goal has been reached in almost every year in the past 50 years.

There are no sales targets or market share goals. There are no central marketing campaigns though local branches can do so at a local level. Fixed salaries, without bonuses, apply to all employees (and executive management) except for a limited number of asset management and investment banking functions.[3] Budgets were abolished in 1972, the view being that budgets pervert behaviour in a business where the ability to manage and minimize risk is essential.

Incentivisation is extraordinarily long term in nature and focuses on after tax returns and a profit share pension scheme called Oktogonen which is entirely based on the group’s share price. One condition for an allocation to be made is that the group reaches its corporate goal, and each employee receives an equal part of the allocated amount, regardless of their position. Over 98% of the group’s employees are covered by Oktogonen and payments to the employee cannot begin until they turn 60 years old. So, the primary mode of incentivization for all employees in the group lasts well into retirement.

We believe this combination of corporate structure and incentives to be uniquely attractive in the sector and incredibly difficult to replicate. It helps to explain why it remains one of the very few banks in the Western world which has never been bailed out, having been tested during the Swedish financial crisis of the early 1990s and, of course, the global financial crisis of 2008-09. During the global financial crisis, Svenska Handelsbanken’s NPLs peaked at just 0.23% of total loans, a level most banks can only dream of even in the very best of times.[4] This historically low amplitude in NPLs means that Svenska Handelsbanken’s earnings stream behaves more utility-like. Trading on 1x tangible book and with a high single-digit yield, we believe the compounding power of its mundane but profitable growth is underappreciated by the market.

Sources:

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/oct/18/llyods-shareholders-mugged-by-2008-hbos-takeover-high-court-told

[2] https://news.sky.com/story/ubs-to-take-over-credit-suisse-swiss-central-bank-confirms-12838193#:~:text=It%20was%20announced%20overnight%2C%20following,action%20to%20boost%20dollar%20flows.

[3] The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

[4]Bloomberg, as at 30th June 2023

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.