In the 1980s TV crime drama series, The Equalizer, and the more recent films of the same name, the ex-intelligence officer turned vigilante, Robert McCall, pursues justice on behalf of innocent people that have been in some way wronged. We aren’t looking to exact justice via this article, but we do wish to explore the inequality that currently exists within equity markets and society, with a view to understanding how they may, over time, normalise.

In the money

Global stock markets have rarely been this narrow. The biggest five stocks now account for 15% of the world index [1]. This handful of US stocks have been holding up the rest of the market, to the extent that, despite all the volatility we’ve seen so far this year, the S&P 500 index is, at the time of writing, only 8% off its all-time high [2]. Rising inflation, the expectation of multiple interest rate hikes this year, war in Ukraine – stock markets have done their best to shrug off all these concerns in an attempt to maintain their upward trajectory.

The headline index level masks a significant disparity within markets. The tech-heavy Nasdaq index has fared worse, down 17% from its November 2021 all-time high, and in March, it was reported that more than half of Nasdaq constituents has fallen at least 50% from their 52-week highs [3]. This suggests that all is not well in the stock market, but the continued positive fortunes of most of the tech titans that dominate the US stock market hides the pain being felt elsewhere.

Some history illustrates that this inequality – between the large stocks that have continued to do well, and practically everything else which has weakened – cannot last for much longer. Recent market behaviour adds to the valuation stretch that has been observable for some time – the expensive stocks have remained expensive, but the cheap ones have become even cheaper.

Breakpoint

It is in conditions like these that genuine long-term opportunities may be unearthed. We remain very wary of the valuation risk that exists among the index behemoths but are increasingly positive about some of the valuation anomalies that are developing elsewhere.

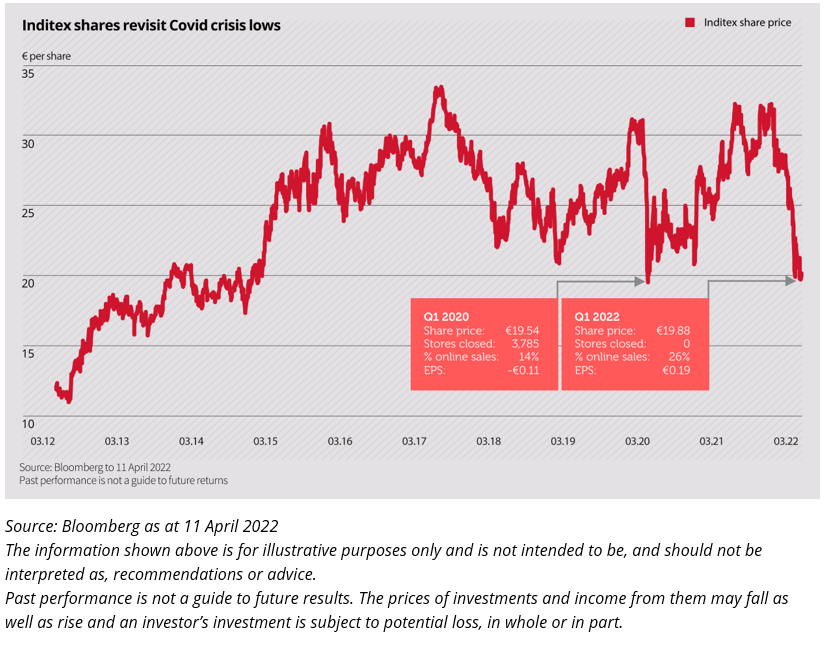

Take Inditex (Industria de Diseño Textil), for example, a Spanish-listed business that is best known for its Zara brand. Inditex is the largest fast fashion group in the world. Life has clearly not been easy for any retailer over the last couple of years. Indeed, in the spring of 2020, all of Inditex’s more than 6,000 physical stores were closed for a protracted period as we navigated the early, unsettling stages of the global Covid pandemic. Unsurprisingly, its share price was profoundly weak during the Covid sell-off, as the chart below illustrates, bottoming at slightly below €20 per share on 16 March 2020[4].

However, Inditex has not been sat on its hands for the last two years. One of its enduring strengths has been its ability to move rapidly to adapt to changing consumer preferences, which is critical in the world of fast fashion and has been a key element of the successful long-term compounding growth story. This cultural focus on flexibility has stood it in good stead through two challenging years during which it has transformed its business. It has launched a revived online sales platform in multiple markets, to successfully pivot its business towards e-commerce. Meanwhile, disciplined management of the cost base has enabled it to maintain gross margins – despite the temporary interruption to its customers’ ability to visit its stores.

In short, the business is in a much stronger position today than it was in two years ago. So, it is surprising to see its share price revisiting the lows of 2020 in recent weeks.

Past imperfect

One further characteristic which we expect to be supportive to the long-term trading environment for Inditex – and indeed for all consumer facing companies – comes through the inequality that can be seen across society more broadly.

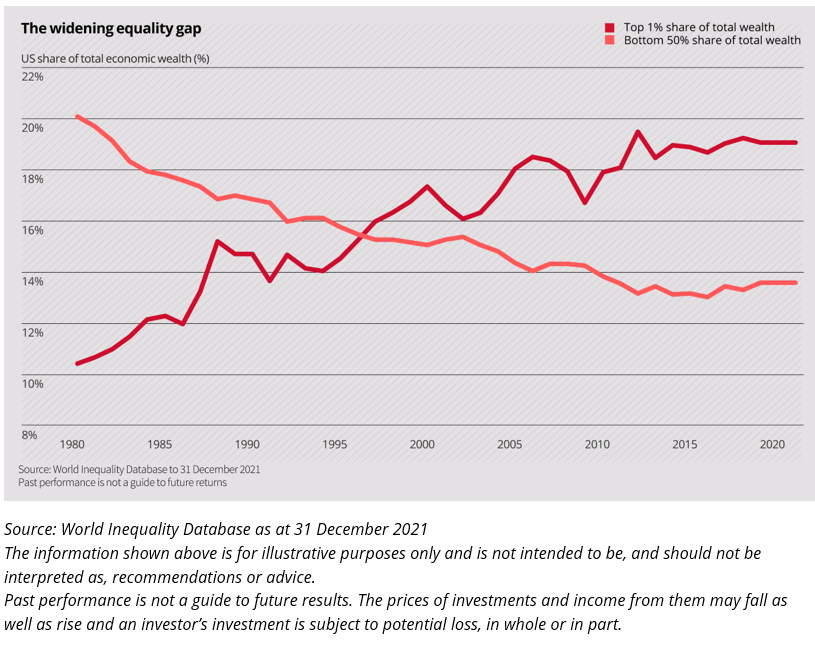

For more than a generation, wealth in most developed market economies has become more and more concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer individuals. The trend is most observable in the United States, but it is by no means confined just to this economy. This equality gap started to emerge well before the era of extraordinary monetary policy, but quantitative easing (QE) has almost certainly played a role by rewarding those who own financial assets, while ignoring those who do not.

We may have crossed the Rubicon here. QE is in the process of being withdrawn, inflation is looking more and more entrenched, and, thanks to aging populations, labour forces are starting to shrink across much of the developed world. In pay negotiations, the hand of the employee looks stronger than it has for many, many years.

Perhaps more importantly, the concept of “levelling-up” is now a political debate. If politicians believe they can win extra votes by vowing to do something about it, they are bound to pursue the cause. Power to the people!

These factors are supportive of the idea that the gap between the wealthy and the rest may be beginning to shrink. The equality gap has taken decades to open and unwinding it will also inevitably take time. Overall, this is potentially a very positive development for consumers and consumer-facing businesses.

Endgame

The prospect of seeing labour gain a greater share of economic wealth is arguably a positive thing, not just for consumer-facing businesses, but for society and the economy as a whole.

This could be a theme which takes a long time to play out and it certainly doesn’t revolutionise the prospects of a retail business over night. But, in our view, it is incrementally positive, and it is something we are thinking about a lot more, as one of the many things we have to triangulate when building the portfolio. Coupled with the compelling valuation attraction that we see in the likes of Inditex, we are becoming increasingly positive about retail exposure within the portfolio.

As for the other inequality – that between the loved stocks and the loathed stocks – this is something which could be equalized much more rapidly. Timing such an eventuality is, of course, impossible to predict with any degree of certainty – even for Robert McCall. But history suggests the current bifurcation in markets cannot last for much longer.

[1] Source: Bloomberg as at 30 March 2022

[2] Source: Bloomberg as at 18 April 2022

[3] Source: Bloomberg / Societe Generale as at 09 March 2022

[4] Source: Bloomberg as at 16 March 2020

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment.

Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part.

The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.