One of the many pleasures of being a parent to young children is watching kids’ movies: relaxing in front of some great animated cartoons that, as a grown up, you’d probably be too embarrassed to go and see on your own. On the pretext of “having to look after the kids”, I recently enjoyed the critically acclaimed cinematic jewel, Kung Fu Panda 4, the latest instalment in the franchise telling the story of Po, the ordinary-bear-turned-hero, a chubby Panda with a penchant for throwing punches (aimed at bad guys, of course).

As Kung Fu Panda connoisseurs will know, an iconic scene in the first movie is when Po – who, as you no doubt remember, is the adopted son of a goose who runs a noodle store – is given the secret ingredient for the Secret Ingredient Noodle SoupTM:

Mr. Ping: The secret ingredient is… nothing!

Po: Huh?

Mr. Ping: You heard me. Nothing! There is no secret ingredient.

Po: Wait, wait… it’s just plain old noodle soup? You don’t add some kind of special sauce or something?

Mr. Ping: Don’t have to. To make something special you just have to believe it’s special.

Leaving aside the inspirational message of self-belief, this exchange – as with every great work of art – contains a profound lesson for the successful investor: sometimes, the secret ingredient is a whole lot of nothing.

By nothing, we don’t mean to imply that one can outperform by putting your feet up in Mauritius with a cold beer and a good book. Rather, the nothing we refer to is in the ability to patiently identify and purchase a portfolio of undervalued businesses – and then to simply leave them alone [1].

The value in doing nothing

Many investors feel the constant pressure to do something: buy, sell, turnover, trade. Whether it is the glare of attention paid to monthly performance statistics, or the sense that earning your keep as an active manager demands constant activity, investors across the market feel this pressure, and many succumb to it. Not only does this incur significant extraneous trading costs, but most likely involves selling several great investments, or buying several poor ones, simply for the sake of having a refreshed portfolio.

Such futile frenzy is exacerbated by the uncomfortable fact that, whilst it is possible to identify that a company is substantially undervalued, it is virtually impossible to predict just when that might change. As such, many investors lose patience with what seem like fundamentally sound investments, selling up with a vague intention of returning when the realisation of the mispricing is nearer at hand. Of course, the issue with demanding the comfort of an explicit catalyst – some discrete event that will unlock the value of an investment – is that we do not believe these are actually predictable, in either magnitude or timing. If and when they do emerge with sufficient clarity, market prices have often increased in anticipation, squeezing out the returns available to anyone who feels that they need to know exactly when their payday will come.

Instead, in our view, the most beneficial approach for investors is to simply identify the very best opportunities – ignoring shiny-and-new but mediocre alternatives – and hold them until they are recognised by the marketplace, no matter when that might be. In this regard, two pertinent facts aid the patient investor.

A disciplined approach to doing nothing

First is to recall that the goal of investing is the long-term compounding of value over time, the sole determinants of which are simply your start and end values, regardless of the pattern of growth in between. This is expressed in a compounded percentage return figure, the effective annualised rate at which your initial investment has grown (although again, critically, not the actual return you earned in any interim year).

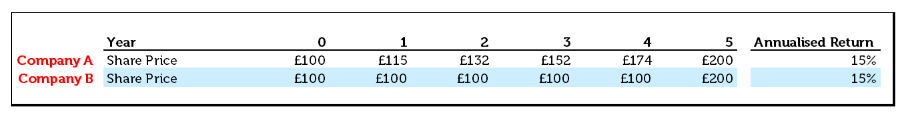

For example, if you invested £100 and ended up with £200 after five years, you would have earned 15% on an annualised basis, a very healthy return. Crucially, what doesn’t matter is when over the course of that five years this return is earned. In the example below, the annualised returns of investments in Company A and Company B are identical after five years, even if owning Company B makes you feel a lot less clever, most of the time:

The information shown above is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or advice.

As a result, what investors should care most about is simply finding the most undervalued companies – which, at some indeterminate point in the future, will invariably have their value recognised – rather than ignoring such opportunities just because they lack an obvious value-realising catalyst. Like much of investing, that is easier said than done, and maintaining the discipline to hold something through long, yawn-inducing stretches of no returns demands a healthy dose of Secret Ingredient Noodle SoupTM’s secret ingredient: just doing nothing. In our experience, as long as you paid a sensibly low price for a company with robust fundamentals, the result will likely take care of itself.

In our experience, as long as you paid a sensibly low price for a company with robust fundamentals, the result will likely take care of itself.

Good things can come to those who wait (while doing nothing)

The second fact that comes to the patient investor’s aid is this: cash generated by investee companies is just as good as that of the marketplace. If a management team is willing and able, they can take advantage of a consistently low share price to repurchase shares, or, at the very least, distribute cash in the form of dividends. In effect, if we have correctly assessed the earnings power of the business, and the company is being managed well, our returns would simply come in a form other than the share price: cold hard cash.

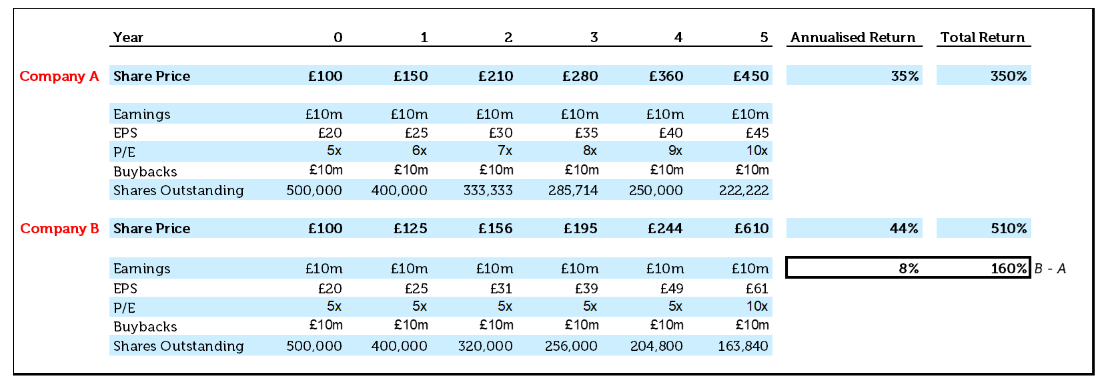

In fact, in such a scenario, a persistent period of low valuation – company B, in our previous example – can be an advantage for investors. Let us assume that companies A and B are earning £20 each per share, placing them both at a price to earnings (“PE”) ratio of 5x at today’s £100 share price. As in our previous example, by the end of our five-year investment period, each have seen their PE ratio increase to 10x, a more normalised level; Company A, however, has seen a steady increase each year from 5x to 10x, whilst Company B sees the entire change all of a sudden in year five. When there are no buybacks involved, the returns for both are the same. However, look what happens to the returns when we assume that the companies spend their earnings on buying back shares:

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment.

In this example, prolonged investor indifference for Company B means that it can take advantage of its lower share price for longer, delivering a whopping 8% better annualised returns for investors than Company A. Over the full five years, Company B delivers £160 more profit than Company A for every £100 invested. Truly long-term investors, then, should prefer buying shares in Company B even though it will demand the sort of patience that many market participants often lack.

Very often the secret ingredient to successful investing is simply being able to sit, be patient – and do nothing (provided you have correctly surmised the investment opportunity).

One particular group of investors who lack this patience, and whose participation in global markets has continued to rise in recent decades, are those who obsess about short-term share price movements. These investors typically substitute metrics such as Sharpe Ratios – the measurement of annual excess return per unit of volatility – for what should be their focus: maximising long-term returns. An investor preference for smooth returns over lumpy ones is, of course, obvious: so obvious as to compel one to wonder why the marketplace would sell these return streams at the same price. If investors prefer smooth returns, they will have to pay up to receive them – at the expense of total performance. This is exemplified in the above scenario: whilst Company B makes its long-term owners substantially richer than those of Company A, its Sharpe Ratio is materially lower – 0.8 compared with 3.1, at a 5% risk-free rate. Choosing an investment based purely upon measures of smoothness, therefore, can clearly lead to worse outcomes for the truly long-term investor, for whom patience typically results in excess return.

Walking with the wise

As our Kung Fu Panda hero Po discovers from his wise father, very often the secret ingredient to successful investing is simply being able to sit, be patient – and do nothing (provided you have correctly surmised the investment opportunity). Indeed, these sentiments can be found beyond the realms of kids’ movies; investment titans Warren Buffett and the late Charlie Munger, each reflecting on the basics of investment success, echo similar sentiments:

“In allocating capital, activity does not correlate with achievement. Indeed, in the fields of investments and acquisitions, frenetic behavior is often counterproductive. Therefore, Charlie and I mainly just wait for the phone to ring.” – Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Chairman’s Letter to Shareholders, 1998

“The wise ones bet heavily when the world offers them that opportunity. They bet big when they have the odds. And the rest of the time, they don’t. It’s just that simple.” – Charlie Munger, ‘A Lesson on Elementary Worldly Wisdom’

Or, in the words of Winnie the Pooh, another venerable cartoon bear:

“Doing nothing often leads to the very best something.”

Sources:

[1] All the while, of course, continuing to monitor corporate performance, and scour the markets for potentially better opportunities.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.