‘While the demographic shift is often presented as a crisis for China, we see immense opportunities in these challenges.’

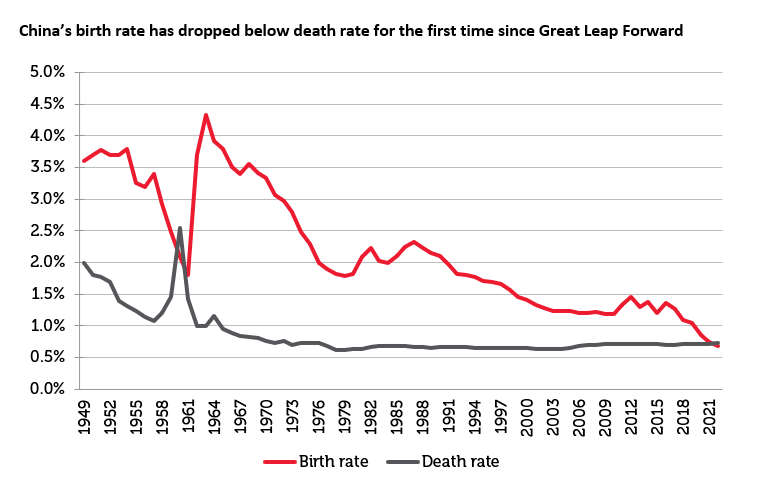

China’s population declined last year, the first annual contraction since 1961, amid a Covid-induced sharp decrease in new births and long-term structural factors. China has followed a similar trajectory to many developing countries as having an aging population is a common demographic problem in developed countries, where birthrates have steadily declined with higher levels of income, healthcare and education. Countries such as Japan and Germany have had decades to adjust as their populations have aged gradually. China, on the other hand, has begun the aging process at an earlier stage of development and at a more accelerated pace than most countries have experienced. In 2022, official statistics revealed a decline in China’s population with a fall of 850,000 from the previous year. However, for a country of more than 1.4 billion people, the difference is relatively small but shows the general trend.

The central government has acknowledged the looming demographic problem with a policy package to boost births in August 2022, pledging to improve public services such as healthcare and childcare as well as to offer priorities on public housing to bigger families. Local governments have since followed suit, rolling out home purchase subsidies or allowances for families with multiple children. Despite China’s population decline often presented as a crisis, we see a number of opportunities as we continue to believe China’s economic growth will be driven by labour quality rather than labour quantity. We expect China’s GDP to potentially grow around 5.5% to 6% in the medium term, within which service sectors should become more prominent.

Source: CEIC, Jefferies as at 31 January 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

Given the forecasted population contraction, many are concerned that the demographic crisis will turn into strong growth headwinds. In our view, the shrinking population may influence total demand, but the negative impact may not be as large or damaging as the headlines suggest. We examine the economic impact of this demographic trend on China’s manufacturing and consumption.

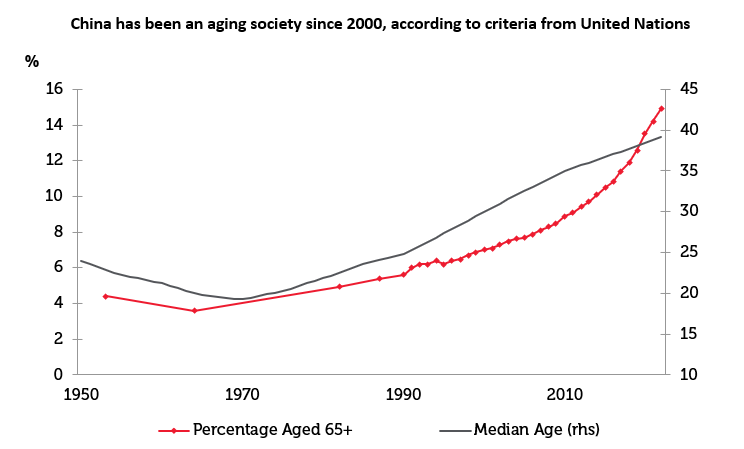

Source: NBS, United Nations, Citi Research, as at 31 January 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

Manufacturing will see little impact

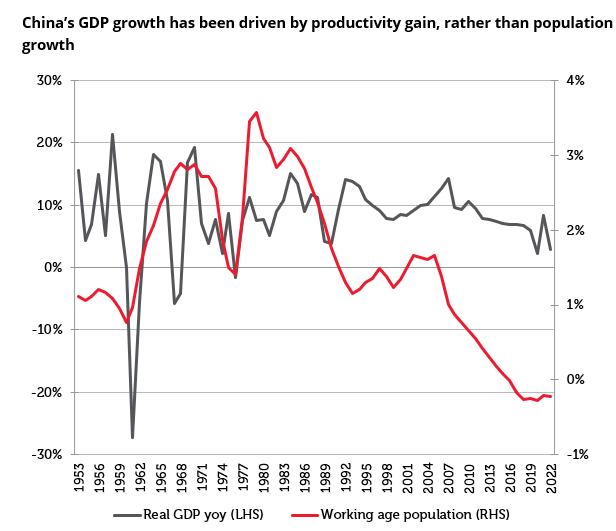

It might be intuitive to conclude that China may lose its edge in some labour-intensive sectors due to higher labour costs caused by a decline in the working-age population. We argue differently, on the basis that China’s growth miracles in the past 30 years were not solely driven by an expansion of its labour force. The working-age population grew 1.4% annually between 1980 and 2019 in the country, while its GDP grew 9.4% annually. Productivity gain is evidently more important in economic growth and will continue to be China’s key growth driver.

Source: CNBS/H, United Nations, Haver, as at 31 January 2023. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

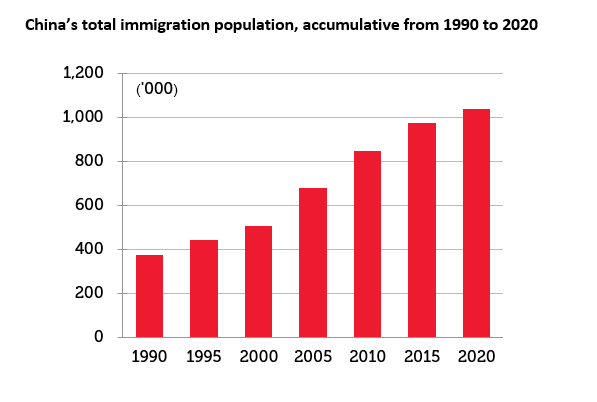

Most developed countries actively increase immigration to mitigate population collapse. However, this is less applicable in China: from 1990 to 2020, China has seen total immigration of merely 1 million. This lack of immigration is due to both language barriers and the country’s restrictive immigration policy. While we do not expect this to reverse in the foreseeable future, we do think that raising the retirement age could enable more workers to stay in the labour force for longer. China currently has the lowest retirement age among the OECD countries. China requires most men to retire at 60, white-collar women at 55 and blue-collar women at 50. That is well below the retirement age of 65 in Singapore, 67 in Germany, and 70 in Japan. The Chinese government has pledged to gradually increase the retirement age by 2025. We believe this could offset some of the impacts from the declining labor force.

Source: United Nations, as at 31 January 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

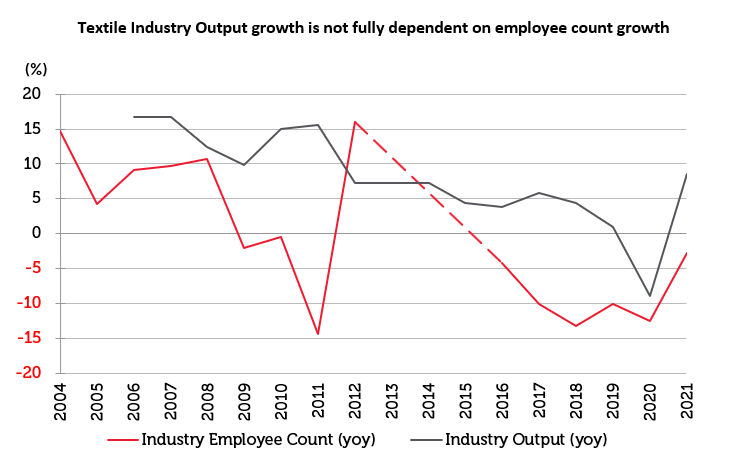

Labour aside, productivity gain should continue to be the key contributing factor for growth. China’s manufacturing sector has seen a strong productivity improvement in the past three decades. Since joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO), China has established massive production scale and expanded into several diverse industries. The economies of scale and comparatively integrated industrial chain have created impeccable production efficiency and cost effectiveness, which offers a significant advantage to other nations in comparison. Looking at the labour-intensive textile industry as an example, in addition to mass production, China’s cost advantage in the textile industry stems from the fact that China leads the upstream production of polyester. China has about 80% of the world’s polyester production capacity, which provides unparalleled cost advantages to local fabric manufacturers and subsequently the garment producers. China, therefore, has remained a production powerhouse in apparel, which might seem to be among the easiest to shift to lower-cost countries. However, China remains at the forefront of FDI inflows into neighbouring regions such as Vietnam as China aims to move up the value chain and give priority to projects which could generate high value products and operate using cutting edge technologies.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, as at 31 January 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future results.

Going forward, we expect China’s productivity to gradually improve. Its productivity gain could come from rising investment in human capital, further urbanisation and technology-driven efficiency improvement.

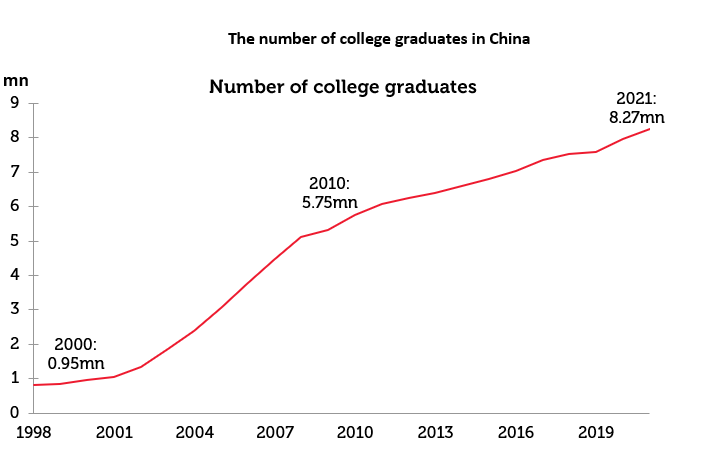

From the human capital perspective, China continues to gain human capital on the back of better education. 7% of Chinese individuals born in the 1960s were able to attend college. The figure became 23% in the 1980s and has reached over 50% for millennials. There is still room for China to increase its stock of human capital.

Source: United Nations, National Bureau of Statistics as at 31 January 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

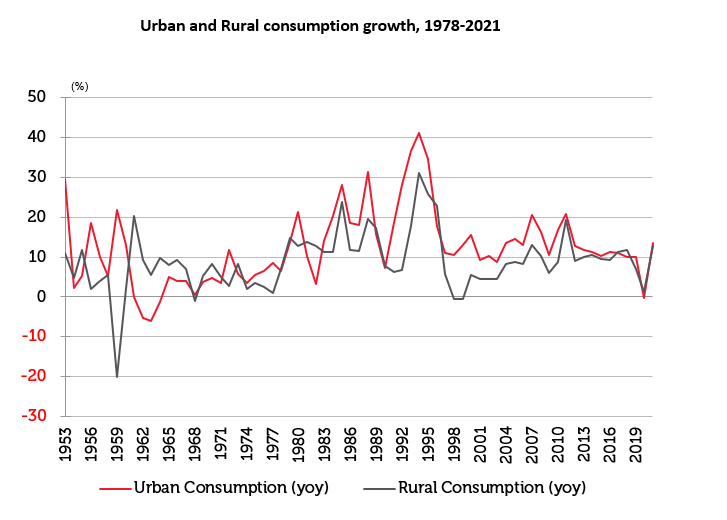

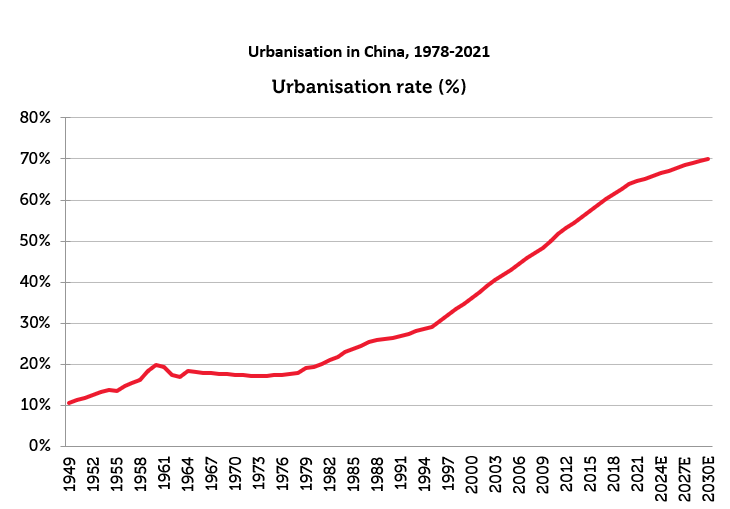

Urban migration has been a major source of cheap labor in China. As people move from villages to cities, productivity tends to increase significantly due to the productivity differentials between agriculture and industry. Additionally, there is a change in consumption spending growth as consumers look to increase spending on property and durable goods, such as cars and appliances. China’s urbanisation rate rose from 36% in 2000 to 65% in 2021, which remains low compared to developed countries such as Japan (92%) and the United States (83%). While facing higher costs, China’s improved labour productivity should allow it to compete with quality in the next wave of industrial prosperity.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics as at 31 January 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

Source: CEIC. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions.

Finally, new technology, such as automation and artificial intelligence, could reduce the demand for labour and extend the working lives of the labour force in general while maintaining output growth. China has been the world’s largest industrial robot market since 2013. With the aid of government policy to push towards automation across industries, we expect China to keep leading in robot adoption and production in the next decade. More importantly, similar to Korea, China is making great strides in high-tech industries in which it still accounts for a relatively small share of global markets, such as renewables, machines, tools and pharmaceuticals.

As a result of these factors, we believe China’s productivity improvement will continue to outweigh the lack of population growth when it comes to manufacturing. We, therefore, see the impact from labour on growth to be minimal.

Unlike manufacturing, consumption should see structural changes

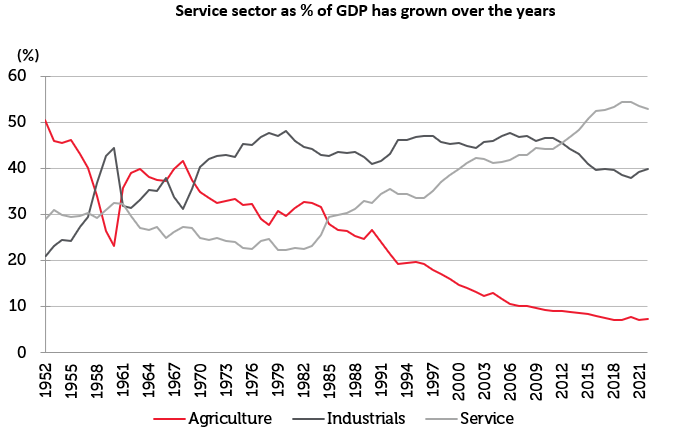

China’s aging population is expected to stay elevated after reaching a peak in 2050, based on UN estimates. This irreversible trend is set to structurally change the country’s consumption demands due to the older consumer having real spending power and different tendencies. Healthcare, consumer services and insurance will be significant in the future. In order to fulfil demand from a silver economy, we expect China to invest in areas such as healthcare management, serviced community, vocational education, wealth management schemes etc. China is still at a nascent stage in most of these areas. As a result, the service sector should continue to grow as a portion of GDP. In 2022, the service sector accounted for 53% of China’s GDP, up from 44% in 2010 and 40% in 2000. The share could rise further in the coming years.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, CICC, as at 31 January 2023. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

Conversely, businesses in areas such as child-care and higher education will face a smaller market cohort should the number of newborns fail to stabilise. These sectors are at a natural disadvantage. We think that population and demographic changes will bring both rising and receding prospects to China’s general consumption. We are selectively constructive in the service sector, where both the policy and market set-up are much more favourable.

While the demographic shift is often presented as a crisis for China, we see immense opportunities in these challenges. We think that China’s economic growth will be driven by labour quality rather than labour quantity, which will partly offset the impact of a declining population. We expect China’s GDP to grow around 5.5% to 6% in the medium term, within which service sectors should become more prominent. Against this backdrop, we are well positioned for opportunities in these growth areas: new technologies, smart manufacturing, healthcare, insurance, and consumer services.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.