In only two generations, the Rothschild family grew their lending operations from their home table in the Frankfurt ghetto into the largest banking enterprise in the world, lending to princes and governments, and sitting at the centre of European commerce. It is no wonder, then, that many investing aphorisms were attributed to the five brothers, each said to contain a fundamental piece of advice about success in finance, business, and life.

One of the most famous – although likely apocryphal – was the quote attributed to London-based brother Nathan Rothschild:

“Buy when there’s blood in the streets – even if it is yours”

An early appeal to the deep value investor, the key message of the quote was simply that, in a crisis, one should look carefully at the facts and act rationally, even and especially when the portfolio punishment at the time happens to be personal. Whilst this holds true as wisdom for investors generally, we think that there is no prospective buyer to whom it applies more truly today than one: companies themselves.

It is a strange irony that, in viewing the stock market as a scorecard for management performance, the C-suite seems sold on the idea of the efficient market hypothesis: sitting across from us at investor meetings, having presented impressive fundamental performances, many managers have their heads in their hands as their shares do nothing but go down; what are they doing wrong? What are they missing that the efficient market knows?

As active investors, we take a different view, and stake our careers – and our investors’ money – on the market sometimes simply being wrong (at least once in a while). So, when our CEOs bemoan their poor share-price report card, we have only one thing to tell them: take full advantage.

If your partners don’t appreciate you, buy them out. It may be your blood in the streets, but if you are confident of your strategy, and you have executed well, there can be better action to take than to use surplus capital to buy back your shares cheaply from those who don’t appreciate you. As we have previously discussed, even a company with average long-term prospects can create significant value for shareholders by utilising a selective, intrinsic-value based policy of share buybacks; this fact is amplified for companies that are executing well and improving fundamentals.

Indeed, when management teams fall into step with value investors, buying their own shares at a significant discount, they are backed by the same comforting fact as we are: reality is very much on your side. When purchasing £1 for 50p, we invert the classic John Maynard Keynes maxim:

“The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”

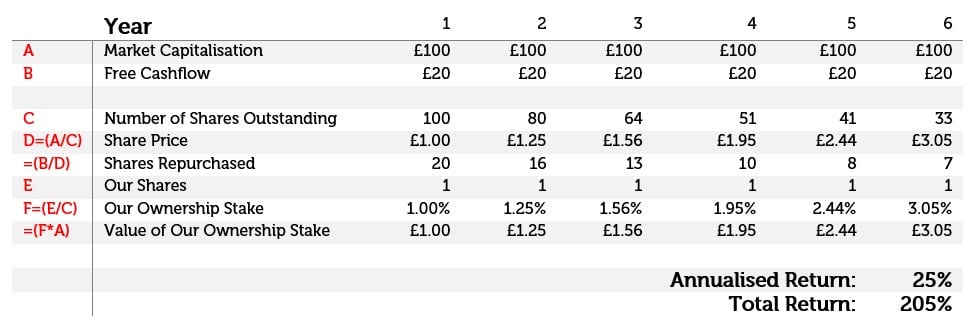

We believe when purchasing high-quality and very real cashflows for eye-watering prices, the market’s irrationality simply cannot cope with the gushing solvency it encounters. If a company is generating £20 of cash for every £100 worth of market value, and its leadership stands ready and willing to buy back their own shares at a discount, there is only so long that the share price can remain stagnant. After all, the company can reduce the number of shares by 20% each year, magnifying the per-share value for those owners who remain. Imagine the scenario, illustrated in the table below: value investors such as ourselves buy a small fraction – say, 1% – of a company that is generating 20% of its market value in cash each year. If the company uses all of that cash to buy back its undervalued shares from a disinterested market – even if we don’t sell or buy any new shares – at the end of five years’ we will triple our ownership stake.

Even if the market remains disinterested, and still values the company at only £100, that means that we now own £3.05 worth of the company, up from our initial £1, tripling our money with no change in corporate valuation, a 25% annualised return. As a reminder, this is in a situation where (i) the market is not in any way increasing the value of the company, and (ii) the company is not growing its earnings in any way.

Source: Redwheel, as at July 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future results.

For those investors paying attention, this dynamic is currently playing out in what is, by many accounts, the cheapest equity market in the world, the UK, with a current pace of c.£200m of corporate buybacks per day, equivalent to £50bn a year. We believe this environment is simply ideal for the long-term investor, who needs to bank on no future optimism to earn their returns. By contrast, if you pay an exorbitant price for a company – yes, even a great company – you are implicitly relying on someone valuing the company at a similarly fancy premium in the future [1], which is simply not a gamble you are taking with cheap, cash-generative companies.

“You will not be right simply because a large number of people momentarily agree with you. You will not be right simply because important people agree with you. In many quarters the simultaneous occurrence of the two above factors is enough to make a course of action meet the test of conservatism. You will be right, over the course of many transactions, if your hypotheses are correct, your facts are correct, and your reasoning is correct” – Warren Buffett, January 1962

Today, a large portion of the market is turning its nose up at exceptional fundamental performance, looking past impressive earnings growth, balance sheet improvements and share count reduction to ascribe enormously less value to the earning power of certain companies, particularly those unfortunate enough to be listed in the UK. This, understandably, can be difficult and disheartening for a company and its management team, who will have worked extremely hard to produce wonderful returns for shareholders. However, for those CEOs who are confident that they have delivered real results for shareholders, and whose facts and reasoning are correct, we humbly offer the maxim: buy when there’s blood in the streets – even when it’s yours.

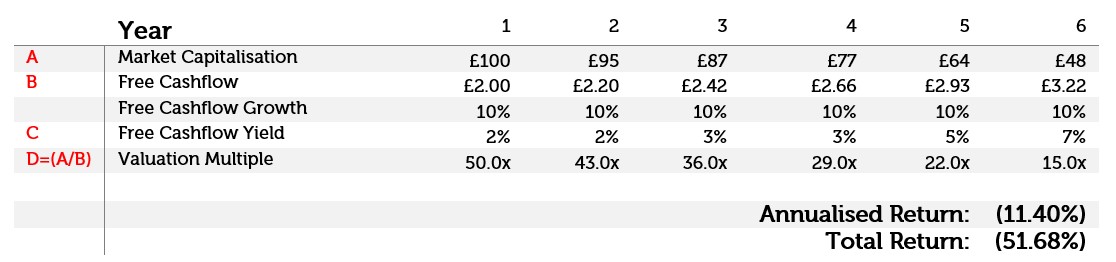

(1) To illustrate this, let us reimagine the table above, except this time, consider what happens when (i) we are buying a great company that is growing earnings, but (ii) we are paying a hefty price for it. In this instance, outlined in the table below, we are paying £100 for only £2 of earnings, or a 50x multiple; even with significant earnings growth – of 61% in five years – investors in the business will lose just more than half their money if the valuation returns to long-run averages:

Source: Redwheel, as at July 2023. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future results.

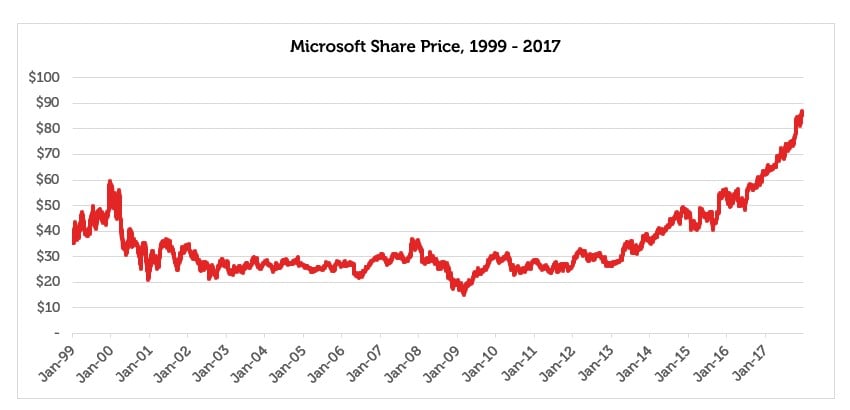

This process explains why buyers of shares in Microsoft in 2000 had to wait sixteen years to breakeven on their investment (and, by 2009, were down 74% at one stage) despite the fact that the earnings per share of the company grew from $0.79 to $2.59 over the same period.[2] It’s not that the business wasn’t very high quality: just that the price paid at the start was far too high. It seems possible, today, that investors paying very elevated valuations for some large US technology stocks may be making a similar mistake.

Source: Redwheel/Bloomberg, as at January 2017. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future results.

Sources:

[1] Morgan Stanley, Bloomberg (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-10/morgan-stanley-strategists-say-uk-assets-are-world-s-cheapest, as at 10th July 2023

[2] Bloomberg/ Microsoft Company Filings, as at 2009

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.