Ah, January. Just the word sends shivers of excitement down the spines of gym proprietors across the world, salivating at the prospect of new year’s resolutioners confidently paying for a full year’s membership, only to slink away sometime in March. Yes, it is the season for attempting to better oneself, and crucial to that effort is self-control and discipline: being able to say no to that sweet treat, and dragging yourself out of bed for that early morning run.

Self-control’s influence on success has been a topic of extensive study, one of the most famous involving four-year-olds, and marshmallows. In the experiment [1], Walter Mischel, a psychology professor at Stanford University, placed a single marshmallow on a table in front of several hundred children (one at a time, mind you). He would then leave the room for a few minutes, and if, by the time he came back, the child had resisted the urge to eat the marshmallow, they would earn a second marshmallow.

Fun as though this experiment must have been – at least for the children – the most interesting results came years later, when the researchers followed up with the now-grown subjects of their study. There was a strong correlation between the length of time that a child was able to resist eating the marshmallow – taken as a proxy for self-control – and their academic test results, weight, life satisfaction, mental health, and earnings. The longer the wait, the better the outcome.

While some dispute the efficacy of this study, the general principle of self-control as a route to success in life is hardly controversial. When it comes to investing, however, we would caution against the alluring promise of additional sweets and advise instead: just eat the marshmallow.

And here is where the key difference between the experimental bonus marshmallow and corporate earnings comes in: waiting for the extra marshmallow may be a good use of self-control when it is promised by a psychologist in a white coat, because you know that it is coming; the same, alas, is not necessarily true with companies. Why wait and rely on hopes that high future growth materialises when you can invest in companies already trading at more reasonable valuations?

As value investors, we look to buy companies at a significant discount to intrinsic value, or the true worth of a business, based on a conservative assessment of its earnings power over time, and the money that will need to be reinvested to sustain that earnings power. A key part of that process is in trying to figure out what the business can earn realistically, and not getting too absorbed in expectations for sky-high earnings growth.

Helpfully, earnings tend to be tied to a number of things, including the assets that the business can utilise and, importantly, what the business has previously demonstrated that it can earn. After all, paying a reasonable price for established earnings doesn’t require great feats of corporate athleticism to turn into a good result for investors.

By contrast, when you pay a large price relative to the historic earnings power, you are baking in assumptions of good-to-exceptional growth; figuring out ahead of time which companies are going to deliver that growth, and which will disappoint, is an almost impossible task. Paying for that growth upfront leaves no room for error: you likely won’t beat the market by being right most of the time if you are betting on the outcomes as certain.

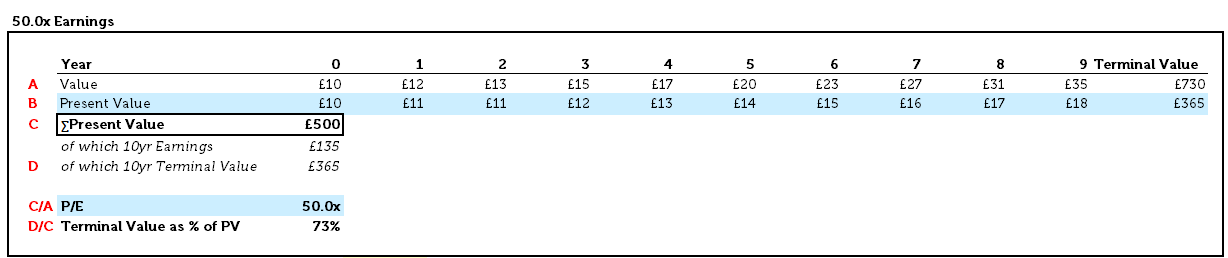

Consider a company priced at 50x its most recent earnings [2]. To justify that price, we need to distil into a single value all the future earnings of the business: the way that this is done is typically by taking a nearer-term picture of income, say, over the next ten years, and then adding on a “terminal value”, the net worth of the business after that forecast – a sum intended to reflect long-run value. These figures are then expressed as a present value – namely, what the sum of the cashflows is worth today – and that present value is the price at which investors buy and sell companies in the market.

To justify a price of 50x current earnings, investors would have to assume that earnings per share grow at 15% each year for the next ten years – a herculean feat – and assume a longer-term growth rate of about 3.0%. Even then, with such staggering success, the price can still only be justified by utilising a required rate of return of 8.0%, which some may see as insufficiently low for the associated risk [3]. Finally, even after generating such incredible earnings growth for ten years, paying 50x today’s earnings means that today’s present value is still mostly made up of the “terminal value”, which represents a whopping 73% of the current asking price:

Source: Redwheel. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

To pay such a price, therefore, investors need to feel certain of the future, certain that by ignoring more reasonably priced companies today – the lonely single marshmallow presented at the start of our experiment – they are going to be rewarded with phenomenal growth for a very long time into the future, and earn themselves an extra marshmallow.

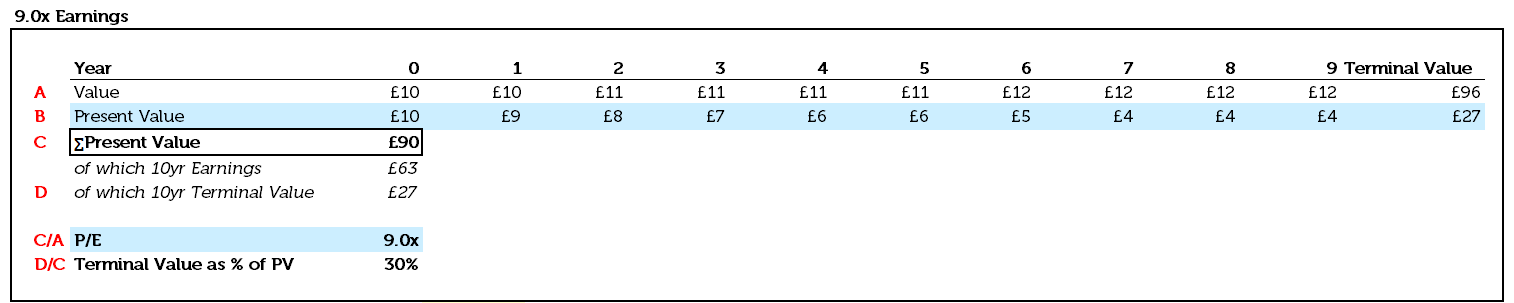

Assuming such extreme growth for such a long time makes value investors like us nervous. If we don’t make any heroic assumptions [4], and pay a much lower price relative to current earnings, the reliance of our current business value on the outcome of the long-term future falls fast, with the “terminal value” comprising only 30% of today’s price, if we pay only 9x current earnings. That means that if both our theoretical companies announced that they were going to cease to exist in ten years, our investment would retain 70% of its value, compared with the higher-priced company, which would be worth only 27% of the price paid.

Source: Redwheel. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes.

We make this point to underscore the importance of thinking carefully about the expectations – explicit or implicit – that are built into market prices for businesses, and the chances of those expectations paying off. Unlike in a lab, in the real economy it is, in our opinion, foolish to assume that more marshmallows will always be forthcoming, and we believe investors should think carefully before turning one down today.

So next time you hear analysts confidently predicting that Company X or Y is going to make $25 per share of earnings in 10 years’ time, and $250 in 20 years’ time – ask them to take out their wallets and bet on it. We, on the other hand, would gladly tell you that we cannot precisely predict what earnings will be in 10- or 20-years’ time, and we don’t need to – because we haven’t paid much for them in advance, preferring to base our view of sustainable earnings power on the demonstrated historical earnings capabilities of an enterprise.

While many are trying to predict the future, we are simply trying to put the present in the context of the past. In the investment world, we find simply eating the marshmallow in front of us requires the most self-control – and can often make the most sense.

Sources:

[1] Mischel W, Ebbesen EB, Zeiss AR. Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972 Feb;21(2):204-18. doi: 10.1037/h0032198. PMID: 5010404. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5010404/)

[2]We can think of a few culprits, who shall remain nameless; one rhymes with Badobe

[3] I would be one of those people

[4] In this case, 2.5% annualised per share earnings growth, a 2.0% perpetual growth rate, and a 15.0% discount rate

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.