For anyone who enjoyed the Olympics this summer, I’d like you to take a moment and spare a thought for Ali Farag. The Egyptian is the highest ranked men’s squash player in the world, according to the Professional Squash Association, and was the winner of the 2019, 2021, and 2023 World Championships. Alas, unlike skateboarders, Farag did not grace your screen at the 2024 Paris Olympics, as squash is still not part of the games, despite it being played by an estimated 20 million people around the world in over 185 countries. Squash is one of the most contentious of the sports not included in the Olympics, among a litany of others including cricket, bowling, netball, darts – and chess.

Chess, unlike other ‘sports’, is regularly dismissed not because of its lack of popularity, but because it lacks the “physical exertion” that the International Olympic Committee demands. Despite the Olympic snub, watching competitive chess online and in person is popular – particularly in the short-form ‘Blitz’ (3-minute) or ‘Bullet’ (1-minute) formats – with international celebrity players commanding audiences of over 600,000 viewers[1]. Chief amongst these celebrities is Norwegian Grandmaster Magnus Carlsen. Regarded by many as the greatest chess player of all time, 33-year-old Carlsen is a five-time World Chess Champion, five-time World Rapid Chess Champion (1-hour games), and seven-time World Blitz Chess Champion. A particularly enjoyable and widely replayed game was a rare defeat that Carlsen suffered in a live-stream he played online; here, Carlsen was playing a Blitz game, and was beaten in 18 moves ending in a highly unusual checkmate.

Blitz chess – apart from being enjoyable to play and watch – is an excellent framework for thinking about investment skill. In Blitz chess, you are not only required to make intelligent moves: you need to also avoid running out of time. It is no good being excellent at identifying the best move if it takes you twenty minutes to do so; you may not lose on skill, but you will lose on time. Having only one of those abilities is insufficient to assure success – and the same is true in investing.

Keep your eyes on the price

As we have noted in the past, investing is a practice that requires, in reasonably equal measure, the ability to (i) understand and quantify the economics of a business over time, and (ii) to fairly assess the value of that business today, what we term the “intrinsic value” of the company. It is only if you are confident in both the earnings stream of a business, and that the price today represents a material discount to the true intrinsic value of the business, that an investment is merited; having only one of those critical elements is insufficient.

In our view, the main mistake being made by many investors today is not about the quality of the business, but the appropriateness of the price.”

Yet, over the past decade, many investors have enjoyed the fruits of a benign economic environment, supported by accommodatingly low rates that made access to capital extremely cheap. This allowed some investors to focus only on the predictability of earnings – part of the assessed quality of the business – while forgetting the importance of considering what the company is worth. Whilst for many years this mistake was swept under the rug of ever-expanding valuation multiples, the landscape today is changing fast, and recent abrupt declines in value of some of the world’s companies shine a spotlight on this error.

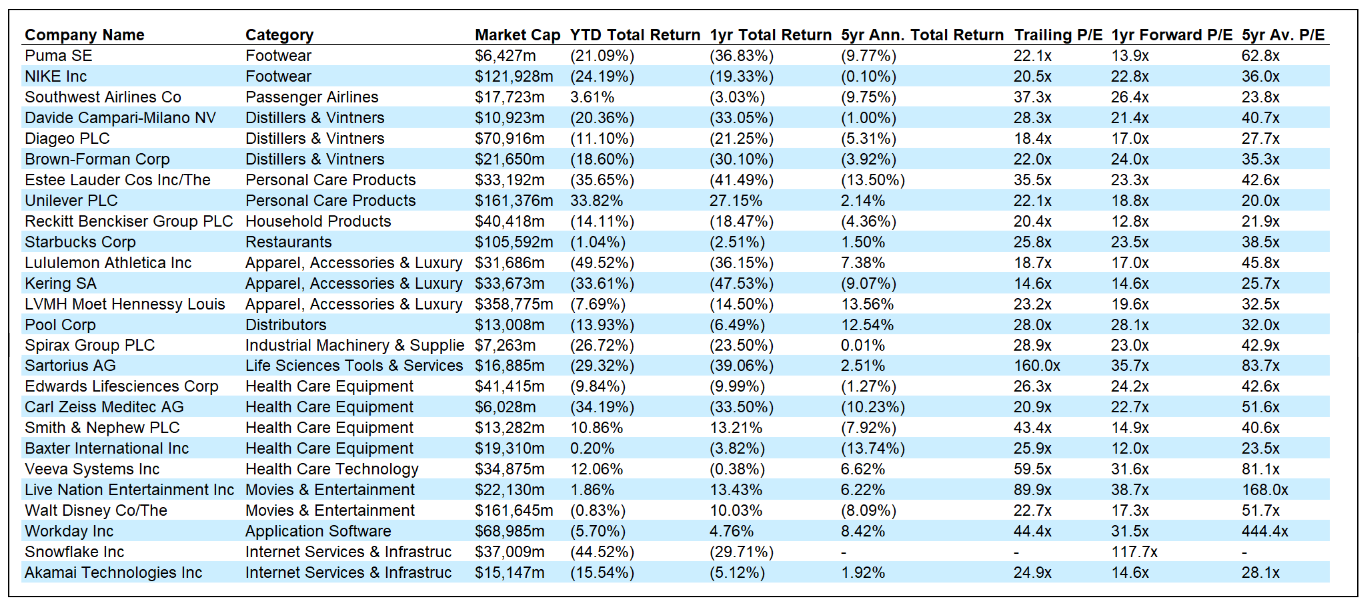

Across industries, geographies, and sectors, many justifiably admired companies have seen their valuations collapse, often leaving investors with zero total returns over substantial timeframes (five years or more). Companies that are widely considered to be global leaders have lost shareholders substantial value in the past year, and many have done so to such a degree as to leave investors with flat or negative total returns over a full five-year period. This is not sector specific, but is a phenomenon found across high-quality industry-leading giants.

Source: Bloomberg as of August 26th 2024 Performance in brackets denotes negative total return. Past performance is not a guide to the future. Stocks selected are for illustrative purposes only and have been identified by the investment team to provide examples of large well-known names that have delivered either negative or below market returns over 1- or 5-year periods.

The question that should arise, of course, is how it is possible that so many truly great companies – great as defined by the quality of their products, the strength of their market position, and the depth of their talent pools – have delivered such poor outcomes to investors? This question is amplified by the relative performance of global markets, which have been comparably strong, and by the simultaneous, very impressive performance of other public companies; again, across industries and geographies, there have been plenty of companies, even those of lower inherent quality, that have delivered fabulous returns to shareholders over the same period. What, then, is the problem?

Quality growth vs value

As with Blitz chess, the answer comes down to the inescapable fact that to win – beating either your opponent, or the market – investors need to be able to balance two skills at the same time. With the above companies, and others, the issue was unlikely to be the quality of the business: rather, it was going to be the quality of the business relative to the price paid, and relative to the expectations baked into those prices. Notably, the connection between the companies in the table above is not the line of business they are in, nor the country in which they operate: it is that they were all highly priced.

For example, spirits manufacturer Davide Campari has delivered no net returns to investors over the past five years. This is largely because its valuation – expressed in shorthand by the multiple of its earnings paid by investors – has plummeted from over 50x in 2021 to 28x today, still by no means inexpensive (if you disagree, I have several banks to sell you). This valuation has also fallen in the context of growing earnings, and continued expectations – despite the share price fall – of future earnings growth. If buying a great business with growing earnings was the sole requirement for investment success, then Campari and the other companies above would have delivered much better outcomes for investors.

As interest rates rise and as highly priced quality companies fail to deliver, we would encourage investors to remember: valuation matters.”

Instead, what has happened appears to be a growing dismissal of the importance of not overpaying, with many market participants having chosen to ignore valuation as irrelevant, relying on the market to constantly pay high multiples. Whilst this approach is all very well whilst the music is playing, it is hard to understand how it can deliver a favourable outcome when the party goes quiet. If you bought Campari at 50x earnings, and earnings grew 15% but the multiple fell to 28x, you would have lost 35.6% – even in the face of impressive fundamental performance. But we would press the question further: who can say that 28x will be the worst price you will get? Why wouldn’t it be 20x (losing you 54%), 15x (losing you 66%) or 12x (losing you 72%)? There are plenty of comparably good businesses that are on similar multiples or lower – usually in unpopular industries – that are available for those prices, and it is very possible that your high-quality but higher valued business will join them.

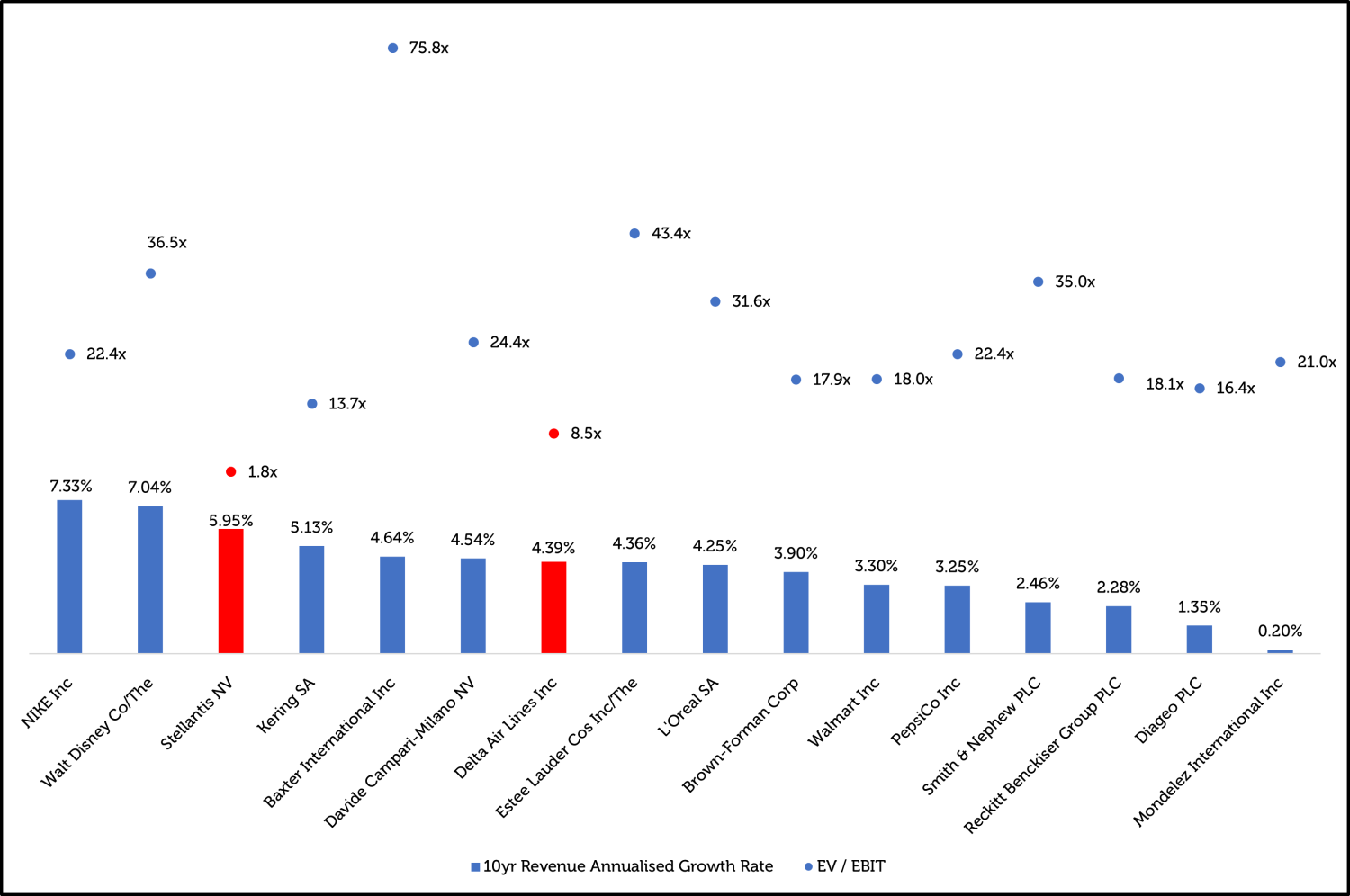

By way of example, look at the below chart, which compares annualised ten-year revenue growth with the enterprise value to operating earnings ratio, a useful shorthand for valuation. Here, it is evident that there are companies (which we own) holding their own against the adored quality growth crowd in terms of long-term revenue growth, but which carry far lower valuations, simply due to the distaste the market currently has for their industry.

Source: Bloomberg, Redwheel as of August 26th 2024. Past performance is not a guide to the future. Companies highlighted in red are securities that the Redwheel Value & Income team currently holds.

If your investment case relies not on fundamental corporate performance – which is in the control of the company – but on a lofty sale price, then the force of economic gravity will do its best to help you lose. In our view, the main mistake being made by many investors today is not about the quality of the business, but the appropriateness of the price.

Avoiding the double punch

That is not to say, of course, that investors haven’t also made mistakes in assessing the quality of a business; there are several companies – some in the list above – that have been lauded for years as perpetual growth machines, only to have recently stumbled, forced to issue profit warnings and temper the lofty expectations of their investor base. Take cosmetics giant Estée Lauder. Despite being priced for prime growth over the past five years – with an average price earnings multiple of 41.2x – the company has had to issue repeated profit warnings over the course of 2023 and 2024, with revenues for the full year 2024 expected to be only 4% higher than those delivered in 2019; net income, what truly matters to shareholders at the end of the day, is forecast to be less than half of that earned five years ago. Not only did investors overpay – they also misread the quality of the enterprise.

This underscores the risk of paying high prices: you are not only relying on the market maintaining its willingness to keep paying up for quality, but you are also running the risk that you are fundamentally wrong about the quality of the business. By stark contrast, when you pay an unjustifiably low price for a company, you are investing on the basis that the core earnings stream of the company is being underestimated, and that things will evolve into a rosier, more normalised picture than is being priced in. If you are wrong, the chances of you losing money is lower; if the company is worse than you expected, it is still in line with what the market expected, and so the market price – right all along – is less likely to change. Buying into a darling company, where everyone expects greatness, can deliver a double punch should there be disappointment with the fundamental performance: not only are earnings lower than you and the market thought, but now the market is less willing to put a high price on those earnings. It has proven for many investors so far this year to be a bruising 1-2 combination.

Valuation matters

Like skinning a cat, there is more than one way to lose money as an investor. It is undoubtedly true that one of these ways is to buy poor quality businesses, whose operation and balance sheet deteriorates, permanently impairing your capital. However, post the Great Financial Crisis – a crisis in which this sort of risk did indeed materialise – investors have perhaps focussed too closely on that risk, forgetting, like the studious chess player who doesn’t check the clock, that there is something else that they need to consider. Today, as interest rates rise and as highly priced quality companies fail to deliver, we would encourage investors to remember: valuation matters.

Source:

[1] https://kommunikasjon.ntb.no/announcement/1062?publisherId=16823864&lang=en

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.