Sometimes, it is better to be lucky than smart. This adage was exemplified in the heat of the Second World War by the British Secret Service’s MI9 division, who were looking for innovative ways to smuggle escape kits to British prisoners of war (“POWs”) held captive across enemy lines.

They had two particularly thorny problems to solve, among others. First was the delivery of said escape kits to POWs: they needed to be provided with tools to cut bars and wires, compasses, and maps of the local terrain. The second problem was the map itself. Paper maps were a poor option, as paper tears easily, dissolves in water, is heavy to pack, conceal, and carry, and rustles noisily when being used. Instead, MI9 aimed to revive an old military tactic by printing maps on silk; silk is quiet, lightweight, and water-resistant. The only problem: virtually no one in wartime Britain had the know-how to print on silk.

Eventually, MI9 tracked down the one man who could do the job, a Mr. John Waddington of Leeds. By sheer dumb luck, Waddington not only provided them with the silk printing facilities they so desperately needed, but he solved their first problem too, giving them a way to covertly deliver entire escape packages to POWs. For Waddington, in addition to being a silk printer, just happened to be the UK distributor of the game Monopoly – a game which MI9 could send to POWs via fake humanitarian organisations, and which had varied enough contents to disguise the many items needed to escape. Compasses and files were passed off as playing pieces, the fake monopoly money had real European banknotes stored in amongst it, and the silk map itself was hidden inside the game’s famous board.

Overall, it is estimated that thousands of British POWs were able to escape Nazi prison camps by using the ingenious Monopoly board escape kits – secretly marked by an extra red dot, printed as if by accident on the Free Parking space. And all because the one person who could solve their printing problem also just happened to have the perfect escape kit disguise at hand.

Passing go: Monopoly’s lessons for equity investors

Monopoly, apart from its less-well known history as a wartime escape kit[1], is the globally recognised board game that brings out the inner entrepreneur in us all – haggling over rents and trying to complete a colour group are no doubt fond holiday memories for many families. For those unfamiliar, the object of the game is:

“To become the wealthiest player through buying, renting and selling property”[2]

This aim obviously aligns closely with the object of investors, who seek to grow their wealth through buying, renting (being paid a regular cash return on invested capital) and selling companies. What is curious, however, is how the behaviour of players differs when playing a board game for fake, paper money, and when investing their own hard-earned money into the very real shares of very real companies.

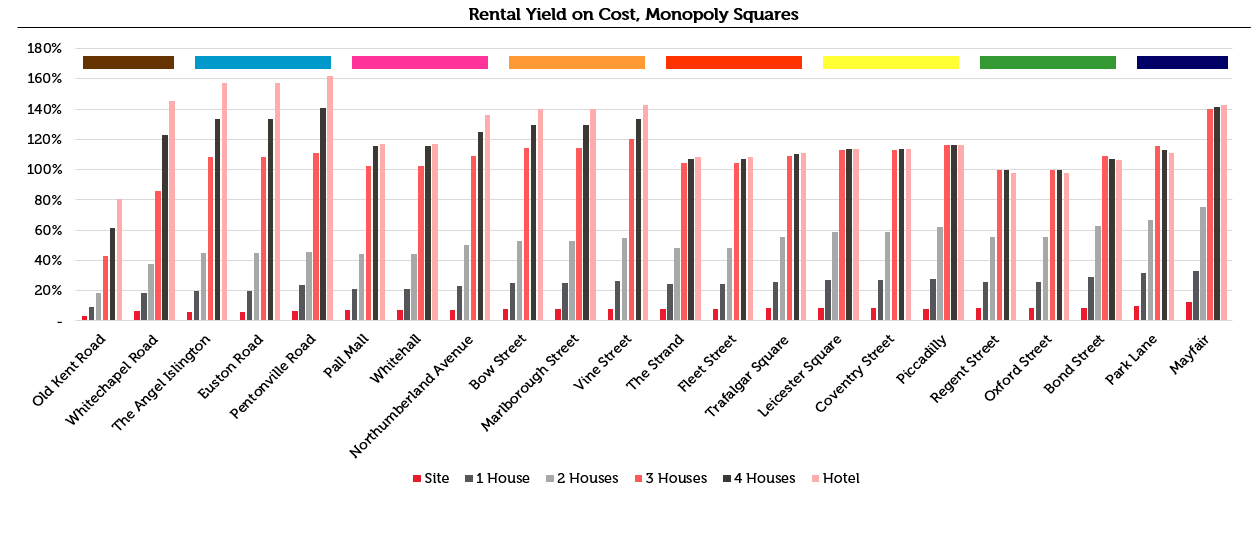

Take, for example, the purchase and sale of properties in Monopoly: the price for each is initially set by the board, and thereafter negotiated between players. Typically, these prices will be closely determined by the ability of those properties to produce cashflow for the owner. Someone with two properties in the orange group[3] will pay more for the third than it is worth to someone without those matching assets, as they can complete a set, build houses and hotels, and earn higher rental yields from their investments:

What doesn’t often happen in Monopoly, however, is wild overvaluation. If someone offers you £20,000 for Whitechapel Road (Baltic Avenue for our American readers) – which is 44x the maximum rent you can earn from the property – you should sell it to them, before watching them go quickly bankrupt whilst you use your money to build cashflow-generating houses and hotels, pay your bills, and remain solvent until victory. Even if someone immediately bought the property off your rash opponent for £50,000, that would not reflect good judgement on the part of the first buyer, or poor judgement on yours: two illogical transactions do not justify one. This fundamental understanding of value as a function of earnings potential, however, seems completely lost on many equity investors.

Not just monopoly pieces

When buying shares listed on public markets, investors seem to instead behave as if they are gambling on the future movements of random lines on a chart – or, in the words of Warren Buffet, like “tokens in a game, like the thimble and flatiron in Monopoly”[4] – represented by abstract ticker symbols vaguely related to some facet of the economy. They forget that, like properties in Monopoly, the shares they are purchasing represent a small but very real interest in a set of cashflows, and that the price of those shares must, over time, be a function of those cashflows. Instead, the price movements of shares – and, by extension, of companies – seems to us to quite often fluctuate to a large extent on short-term directional shifts, such as changes in business momentum or reported earnings.

Any businessperson with a degree of experience will recognise the irrationality of such an approach. Viewed logically, the true value of a company is a simple calculation that evaluates all the likely cashflow a company can produce and when it can produce it, before putting a present value (i.e. what all future cashflows are worth today) on those figures. This, what we term ‘intrinsic value’, should be the north star to a businessperson in the position of a private owner. Although it is always the case that things might be getting better or worse for the business in any given week, the general pathway of cashflows over long periods of time – ten years or more – is unlikely to have changed materially as a result of short-term news flow. If a private buyer wanted to negotiate the purchase of a company, and drastically altered their purchase price on a minute-by-minute basis based on the headlines in that day’s newspaper, they would probably find themselves politely escorted out of the boardroom. If regular business owners can manage quite rationally without paying attention to minute changes in real-time news flow, then perhaps so can we.

The term ‘intrinsic value’ should be the north star to a private owner.

The recent events playing out in the UK corporate market, which we view as among the cheapest in the world, support this point. As valuations are ground lower and lower by what is, in our opinion, a prevalence of short-term pessimism, calmer and more rational actors with a longer-term view – corporate buyers – have stepped in to take advantage. In the first half of 2024, the UK saw £68bn worth of M&A deals[5], a whopping 66% increase over the £41bn in the same period in 2023. Globally, the increase was only 5% year on year: the UK far outstripped global corporate activity, which we suspect is the unsurprising result of its low valuation. This has been reflected in our portfolio, where several of our holdings – Curry’s, Direct Line Group, and Anglo American – have fended off substantial bids from strategic buyers.

Of course, anyone who has ever played Monopoly will intuitively understand what we are describing. Imagine playing with an opponent – let’s call him ‘Mr. Market’ – who takes enthusiasm for the game to a whole new level. As you are playing, he is analysing the wear and tear of the dice, the weight of the game pieces and the direction of the wind in the room, all in the name of trying to discern who will do what next. In so doing, he gets extremely excited about certain squares, and hugely pessimistic about others, offering to transact on those properties at absurd prices – both high and low. It may be true that one player rolling a 5, and skipping happily past Mr. Market’s hotel on Regent Street (Pacific Avenue), is a marginally bad outcome for Regent Street. But over time, the cashflows that an owner can expect to receive from that property will not have changed much. If Mr. Market turns sour on his hotel on Regent Street because of that single roll, and offers it for sale for a mere £600 (just under half its rent), you should snap it up [6]. Similarly, if he sees you cashing in £2,000 of rent from your hotel on Mayfair (Boardwalk), and – marvelling at the high quality of that location and hotel – offers you £100,000 for it, you should sell it to him as fast as you can.

The benefits of irrationality

Intuitively, playing with this kind of opponent is a boon. You get to take advantage of irrational behaviour, which extrapolates recent trends out of all proportion and ignores the future cashflows that each of the properties can be expected to generate.

Despite this, what seems obvious in board games often goes unheeded on the stock exchange. Traders furiously transact on titbits of news, share price momentum and narratives that dominate the headlines. Meanwhile, these same companies continue to plod along, generating cash, investing for growth, and building businesses that measure their results in quarters, years and decades. For those investors who are able to think about returns over similar periods of time – years or decades – the existence of ultra-short-term focussed opponents can be viewed, as in Monopoly, as a benefit.

Another outcome of this fixation with incremental developments is how they impact share prices when news is released. Instead of rationally considering how a company’s announcement may impact the sum of future cashflows discounted to present value, share prices seem to react sharply, jumping or collapsing on good or bad news, respectively.

Investors forget that, like properties in Monopoly, the shares they are purchasing represent a small but very real interest in a set of cashflows.

However, such movements in prices rarely seem to consider the starting point of the company valuation. To return to our Monopoly analogy, it is akin to increasing an irrationally high valuation of Mayfair from £100,000 to £125,000 just because someone landed on your hotel, and you earned a £2,000 payday. Sure, more cashflow is great, but what expectation of total rent did a price of £100,000 assume? Aren’t those large rent cheques already being accounted for in the price? If you’re expecting a surprise, then it isn’t a surprise. And granted, losing a £1,275 rent payday to someone skipping past Regent Street is irritating, but should that push the value of that square from £600 to £400 simply because the event was negative? After all, how many rental payments do you have to collect to earn a handsome return from a £600 purchase price? In our view, these reactions are symptomatic of the prevalence of short-term thinking in the marketplace – a symptom which can provide longer-term investors with attractive opportunities.

All things being equal, we prefer to invest in a market where people sometimes sell us decent quantities of sound businesses at incredibly low prices. The challenge to which we must constantly rise, therefore, is in remembering what we have set out to do, and thinking always about the north star: buying companies for less – ideally, substantially less – than what we think they are truly worth. As in Monopoly, so in investing.

[1] And its less well-known intended function as an advertisement for Georgism

[3]There are eight colour groups, each consisting of four properties.

[4] Chairman’s Letter to Shareholders, Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report, 1987

[5] PWC Global M&A Industry Trends Report, July 2024

[6] You should only snap it up if you expect at least 20 more plays of the board.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.