A wake-up call for investors in the AI era

Global markets are in the grip of Artificial Intelligence (AI) euphoria. Current valuations[1] imply that AI will change everything, revolutionising industries and reshaping the way we work, travel and communicate.

Central to the investment narrative is the expectation that AI will unlock massive productivity gains: automating processes, cutting costs and driving long-term profitability.

But is this expectation justified? Does history support the assumption that technological innovation drives sustained productivity growth? And what lessons can investors learn about how to navigate periods when the focus on the promise of an innovation eclipses all else?

Adoption is accelerating

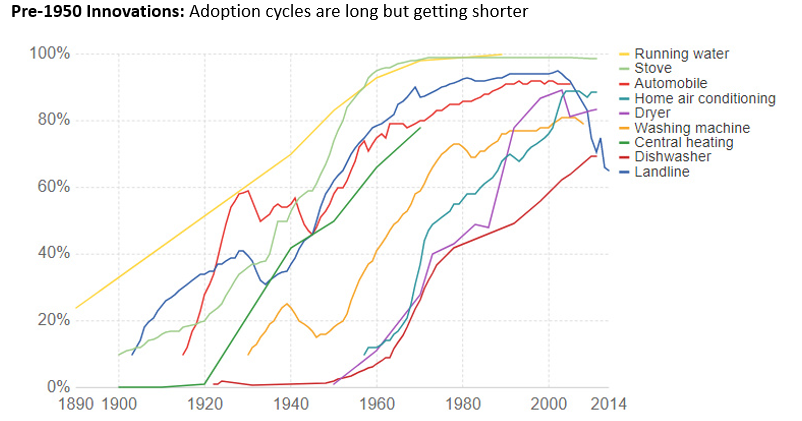

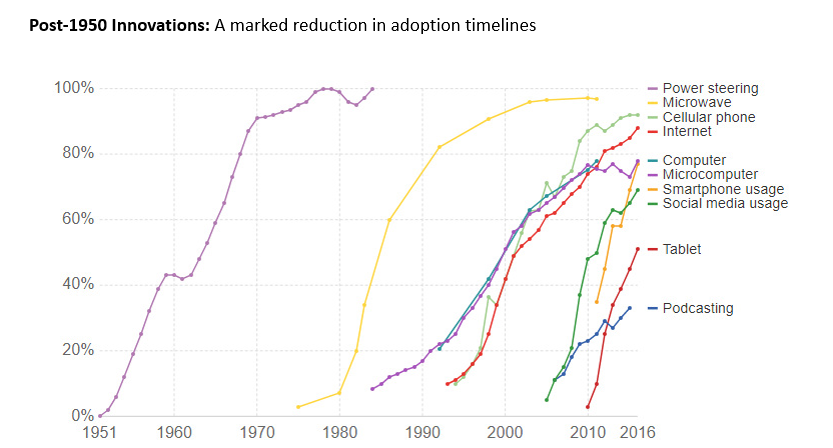

A look back at historical innovations reveals a dramatic shift in the pace of adoption over the last century.

The chart below shows the adoption timelines of key innovations that emerged in the first half of the last century. Technological advancements such as electrical appliances, cars and telephones – tangible and physical innovations – took decades to achieve widespread adoption in a non-digital world. Yet, over this period one can see that adoption cycles are becoming faster, due mainly to the growth in mass communication.

By contrast, the post-1950 period witnessed the rise of digital technologies in an era of mass media and globalisation. Modern innovations—like the internet, smartphones, and now AI—spread at breathtaking speeds, propelled by global connectivity and the network effect.

Given these accelerating adoption rates, it seems reasonable to expect that AI’s adoption will be swift, with corresponding impacts on productivity. Companies and consumers alike are already integrating AI into processes and products, from generative chatbots to advanced robotics. But will faster adoption equate to long-term productivity gains?

A century of unprecedented innovation

To answer that question, we begin by reviewing a century of extraordinary technological advancement. The chart below highlights six technological waves or eras, each of which has had a profound impact on our lives and industry. Together, they have dramatically altered the way we manufacture, work, consume and communicate, improving our health, longevity and quality of life. Surely this has had a beneficial impact on real GDP growth.

Mainframe and early computing

Internet

Cloud computing and big data

Personal computing

Mobile and social media

AI

Source: Redwheel, November 2024. The information shown is for illustrative purposes.

Innovation and its relationship with economic growth and productivity

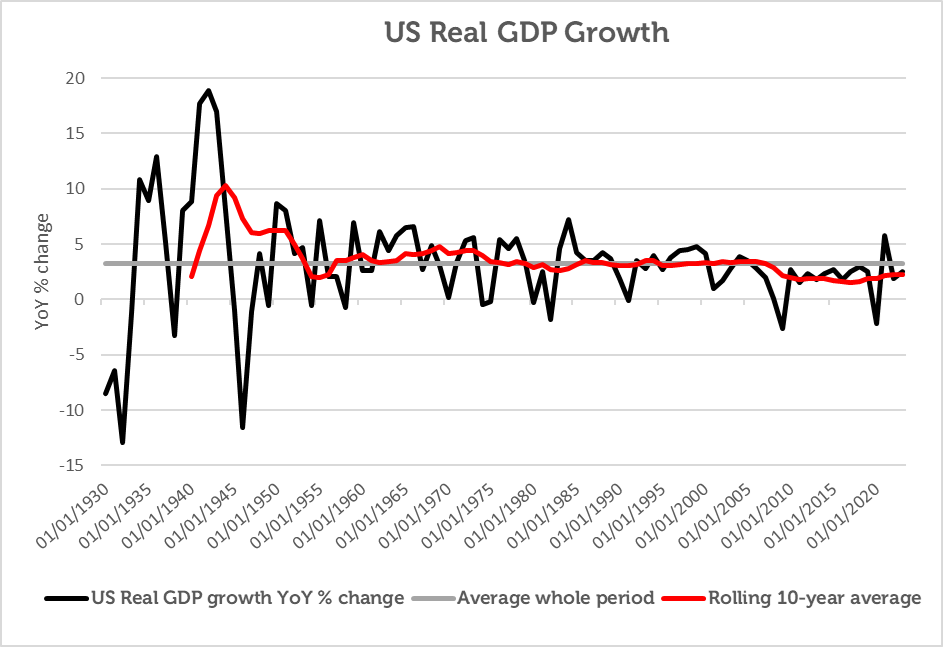

1. US Real GDP Growth is in secular decline

However, an analysis of US real GDP growth since the 1930s reveals a slow but persistent decline in the long-term growth trend. Despite the pick-up during the later years of WWII, overall economic growth has fallen below its historical average of 3.3%. This decline persists despite successive waves of major innovations, from electrification to the digital revolution.

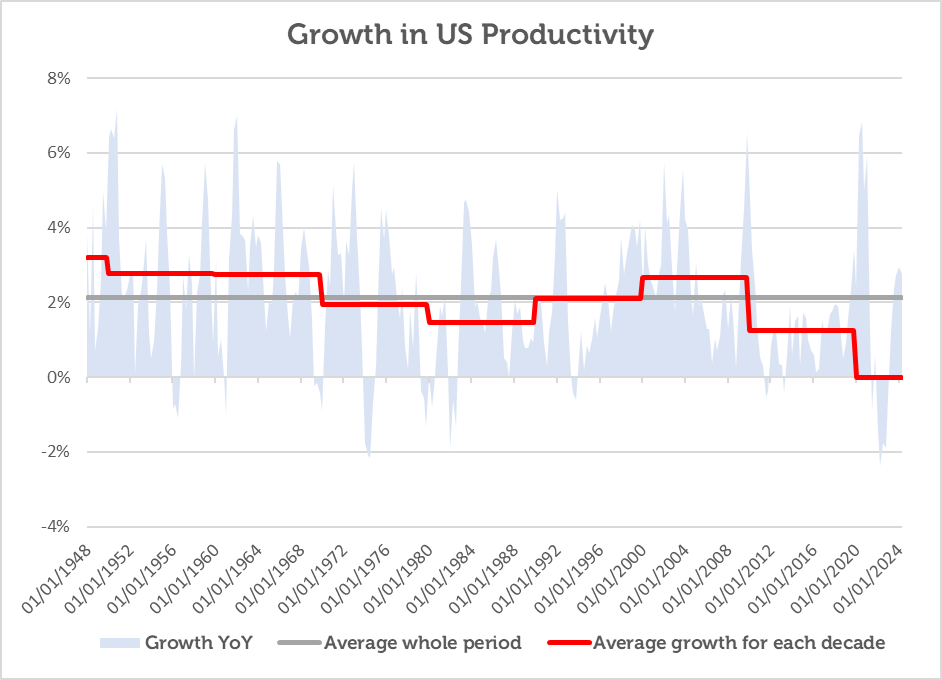

Perhaps waning GDP growth has been compensated by a pick-up in labour productivity growth. This measure looks more specifically at the increase in goods and services produced by the US labour force per hour.

Here again, we see a slowdown in 10-year average growth rates. The data points to declining efficiency gains over time despite meaningful innovation revolutions and the emergence of PC’s, jet planes, satellite, email and the internet.

2. US Labour Productivity Growth is also declining

The notion that innovation leads to a marked shift in either economic growth (as measured by GDP) or an increase in productivity seems misplaced. It would appear instead that innovation is a necessity to simply keep economies moving forward, albeit at a slower rate. If anything, more innovation is needed, adopted quickly to arrest declining productivity growth.

Understanding the productivity paradox

The paradox of innovation is that while it undoubtedly enhances specific processes or industries, its broader impacts on productivity often fall short. This is likely to be due a litany of complex and interwoven factors concerning macroeconomics, labour market dynamics and demographics.

However, one key observation is that increasing efficiency often comes with additional complexity and volume. For example, email dramatically reduced the cost and time of communication compared to letters or faxes, but the ease of sending emails has led to a significant increase in message volume, distracting workers and diluting efficiency gains.

Other factors include diminishing marginal returns at scale and systemic complexity. Innovations often introduce complexities that require new skills, infrastructure, or regulatory frameworks, which can mute productivity improvements.

The impact of speculative euphoria on innovation cycles

This realisation that there is no discernable link between potentially game-changing innovation and productivity growth casts a new light on the excessive optimism that innovations can inspire. As we are seeing with AI today, investors invariably believe that ‘this time it will be different’: capital floods into the sector, valuations soar, and speculative behavior intensifies.

Ironically this capital over-supply tends to aide adoption rates, but it does so by commoditising it. It tends to increase competition and lower entry barriers, creating a high volume of similar options.

For example, the internet era witnessed a surge in speculative investment, particularly during the dot-com bubble. While the internet undoubtedly transformed communication, commerce, and data access, its widespread adoption led to over-supply and commoditization. Cloud computing, too, has transitioned from a disruptive technology to a standard offering, with margins compressed by competition.

In the pre-digital era, utilities exemplified this process. Electricity and power grids were once revolutionary, promising exponential growth as they brought energy to homes and businesses. Early investors flocked to these sectors, expecting sustained high returns. Over time, however, these utilities became commoditized and regulated, shifting from growth investments to stable, income-generating assets. Their perceived value now lies in reliability rather than innovation.

The potential implications for AI investors today

Will AI follow this trajectory, evolving from a transformative force into a utility-like commodity? The pattern appears to be repeating with generative AI set to receive an estimated $300bn in cloud investment by 2030[2]. Markets are pricing in expectations of universal adoption and dramatic impacts on profitability, particularly for chipmakers and AI service providers.

However, as history demonstrates, widespread adoption of an innovation tends to commoditize the technology, reducing its margins and long-term value. Similar dynamics could play out for AI, where increased competition and accessibility may erode the premium associated with early-stage innovation.

Investors therefore need to exercise caution. Unfortunately, it can be hard for allocators to resist the appeal of stocks whose upward trajectory shows no signs of stalling. Fear of missing out dominates, ensuring that bubbles and ensuing concentrations forever reoccur in markets. This is why we believe strict investment disciplines are essential.

The importance of investment disciplines

In the face of innovation hype, disciplined investment strategies serve as essential guardrails to protect against irrational exuberance. Valuation-based approaches help investors navigate speculative bubbles and focus on durable long-term returns.

To illustrate, the Redwheel Global Equity Income Strategy incorporates stringent yield disciplines – both buy and sell – to maximise the statistical power of dividends. The investment team can only buy stocks that yield a greater than 25% premium to the world index. This is of course just one aspect of a broader stock selection process that incorporates rigorous fundamental and valuation analysis. Each stock must offer a compelling combination of yield, durability and positive valuation asymmetry – a combination typically only seen during periods of controversy.

Perhaps more relevant in the era of Magnificent 7 dominance is the sell discipline, which must be sufficient to protect against the behavioural biases associated with excessive valuations. The Strategy’s yield discipline enforces the sale of a holding that yields less than the market, either from yield contraction or dividend-related company decisions.

In the first scenario, the change in yield relative to the market signals that the stock is no longer controversial, the market now accepts the once-contrarian investment thesis and the stock’s risk reward asymmetry has become skewed to the downside. The investment team can then exit the position having correctly identifying a temporary mis-valuation.

This process was exemplified recently when the team closed positions in chipmaker TSMC, which is strongly exposed to the AI investment theme. Reductions began in June 2024 as the dividend yield fell below the market following continued strong performance. Continued upward momentum well beyond intrinsic value prompted the team to eventually close the position in full in September.

Achieving durable returns amid AI euphoria

The allure of innovation will always captivate markets. From electricity to the internet and now AI, transformative technologies offer the promise of reshaping economies and driving prosperity.

Yet both real GDP and Labour productivity are in secular decline. As we have shown above, far from boosting long-term productivity growth, innovation is required to simply sustain it. AI could yet bring substantial change, but like past innovations, its adoption could also lead to commoditization and moderated long-term returns.

For investors, the challenge lies in balancing participation in innovation-driven growth while maintaining discipline to avoid speculative excesses. We believe that by focusing on investment strategies with strict valuation-based disciplines, investors can position themselves to benefit from innovation without falling victim to its hype.

Sources:

[1] Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla comprise over a quarter of the S&P 500 by capitalisation, as at 31 October 2024

[2] Goldman Sachs, ‘Cloud revenues poised to reach $2 trillion by 2030 amid AI rollout’, September, 2024

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.