...and the importance of sensible capital allocation

“When a Chief Executive Officer is encouraged by his advisors to make deals, he responds much as would a teenager boy who is encouraged by his father to have a normal sex life. It’s not a push he needs.”

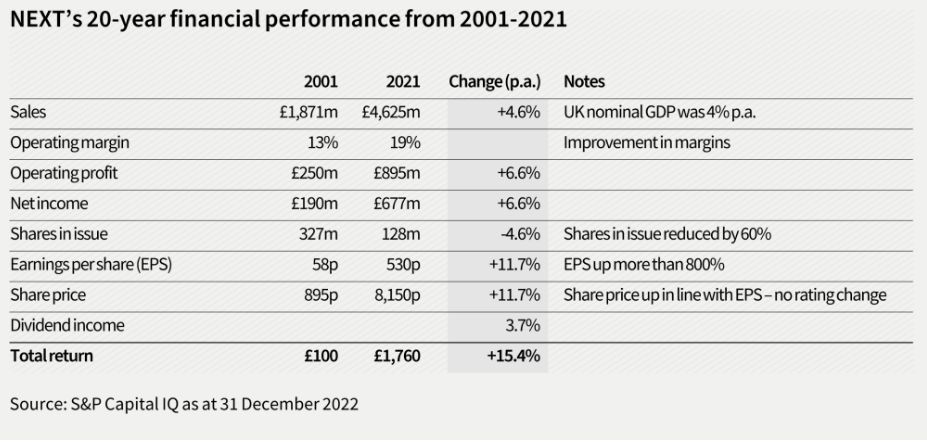

If I told you that there was a UK stock in which if you had invested £100 in 2001, it would now be worth £1,760, which sector would you guess it was in? Technology or maybe biotechnology? What if I told you it was a retailer!?

I suspect you would think that it must have been a small start-up in 2001 that grew through a series of deals like Philip Green’s Arcadia Group or Mike Ashley’s Fraser Group. You would be shocked, therefore, to learn that it had its origins in a gentleman’s tailor called J. Hepworth and Sons which was established in Leeds in 1864, and that it had been around in its current guise since 1981 when Hepworth bought a chain of rainwear shops called Kendall’s and changed its name to…

…NEXT.

I suspect you may now be saying to yourself that you didn’t realise that NEXT’s profits had grown at that phenomenal rate for the last twenty years and the funny thing is, you are right. They didn’t. Sales for the group grew from £1,871m in 2001 to £4,625m in 2021, an annualised growth rate of just 5% per annum, which is less than 1% a year faster than UK nominal GDP through the period.

At which point, you must be thinking that there is an error in my calculations because there is no way that a retailer growing at just above the rate of UK GDP could turn an investment of £100 into £1,760 in just twenty years. So, let me show you how they did it in the table below.

Source: S&P Capital IQ as at 31 December 2022. Past performance is not a guide to future returns. No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment.

Whilst sales may have only grown by 4.6% a year, operating leverage and good control of costs meant that operating profits grew by 6.6% per annum, and the company’s operating profit margin expanded from 13% to 19%. The company’s net income (after its interest and tax) also grew by 6.6% per annum, but here is the clever part.

Throughout this period, the company used its surplus cash flow to buy back its own shares, which meant that the shares in issue declined by 60% from 327m to 128m. As a result of this reduced share count, the earnings per share increased from 58p to 530p, which is an annualised growth rate of nearly 12% per annum. In addition, shareholders received an annual dividend equivalent to 3.7% per annum, turning the 11.7% capital return into a total return of 15.4% per annum.

So, what can we as investors learn from this story of success?

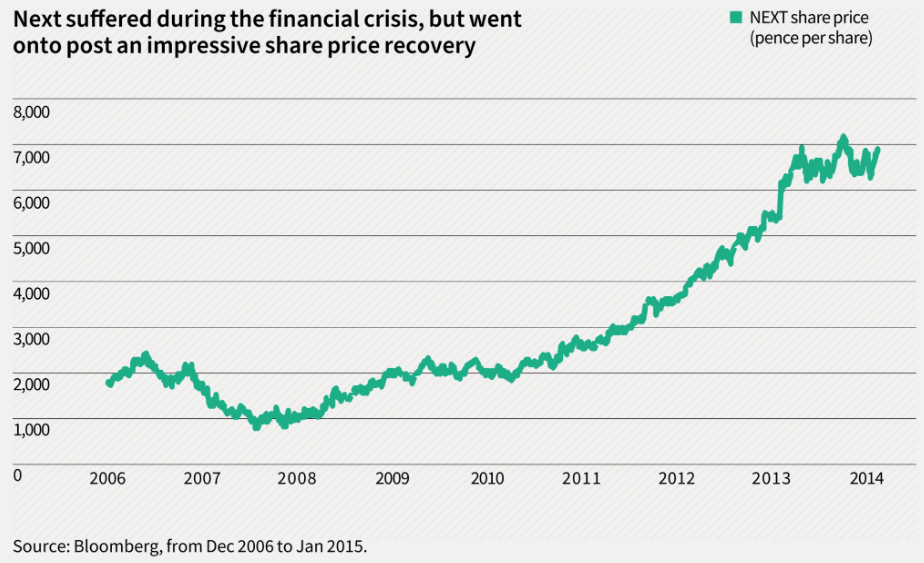

Lesson one: Cyclical stocks can produce attractive long-term returns

On average, NEXT’s sales grew by almost 5% per annum between 2001 and 2021, but NEXT is a cyclical company which suffered during the three economic downturns that occurred during the period (operating profit fell 10% in 2008, 15% in 2016 and 40% in 2020)[1]. Lesson number one is, therefore, that cyclical stocks can produce good long-term returns, and if you buy them during a downturn when the share price is typically depressed, these returns can be significantly enhanced. By way of example, during the global financial crisis, NEXT’s share price fell from £25 to below £10. By 2015 it had recovered to £76, a return of more than 700% from the lows.

Source: Bloomberg, from Dec 2006 to Jan 2015. The information shown above is for illustrative purposes. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

This lesson is particularly pertinent today, as the share prices of cyclical companies are once again trading at very low valuations, which should be a precursor to a period of good returns when the economic cycle recovers.

Lesson two: Sensible asset allocation is one of the key determinants to long-term returns

The same person, Lord (Simon) Wolfson, has been chief executive of NEXT throughout this entire period, which is remarkable in a world where the average tenure of a FTSE 100 CEO is just under seven years. The outstanding returns to shareholders highlighted above are arguably therefore a function of his astute asset allocation decisions which did not involve making lots of acquisitions (in fact, we believe that the returns were this good because he did not make lots of acquisitions).

In addition, during a period when investment returns were nearly always improved through the use of leverage (ask nearly any buy-to-let landlord), NEXT maintained a strong balance sheet and financed share buybacks through internally generated surplus cash flow.

Finally, shares were only repurchased when they were cheap. Any share buybacks were subject to achieving a minimum 8% equivalent rate of return (ERR)[2]. At times when this hurdle rate could not be cleared because the shares were not cheap enough, the buyback was simply paused. Thus, the second lesson is that the asset allocation policy of the CEO can be one of the key determinants of long-term returns to a company’s shareholders.

Lesson three: Buying back shares can be a very sensible use of shareholders’ funds

The ‘dividends good, share buybacks bad’ narrative you hear from (mostly income) fund managers, is overly simplistic in our opinion. Sometimes, it makes more sense to use surplus cash flow to buy back shares than to make any alternative asset allocation decision. It all comes down to a company’s judgement of intrinsic value. If a company’s share price is trading below what it considers to be its intrinsic value, buying back its own shares has one of the best risk-return payoffs of all asset allocation decisions, because that company is in a better position than anyone else to estimate its own value.

Warren Buffett opined on this subject in Berkshire Hathaway’s 1984 letter to shareholders:

“When companies with outstanding business and comfortable financial positions find their shares selling far below intrinsic value in the marketplace, no alternative action can benefit shareholders as surely as repurchases.”

By contrast, paying a premium to buy somebody else’s company has one of the worst risk-reward payoffs, since the seller has the information advantage. The only thing worse than this is paying a premium to get into a completely new business area (a folly dubbed ‘diworsification’ by Peter Lynch, legendary fund manager of the Fidelity Magellan fund in his book ‘One Up on Wall Street’).

Conclusion

Needless to say we will be actively encouraging the management teams of businesses within our strategy to allocate capital sensibly. Typically, that will mean discouraging acquisitions that can erode shareholder value and supporting buybacks if they can enhance long-term returns.

With the share prices of many incumbent operators trading at such low valuations, the risk-reward of a share buyback looks much better to us than highly-priced acquisitions in new areas. Buying back shares may be significantly less exciting than making big new acquisitions but as the case study of NEXT demonstrates, sometimes boring is good.

Sources:

[1] Source: Bloomberg

[2] ERR is calculated by dividing the anticipated pre-tax profits by the current market capitalisation

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.