Why rare market conditions demand a return to investment fundamentals

2025 is a rare year. It’s a perfect square (45²), the sum of cubes from 13 through 9, the first perfect square year since 1936 and the next one won’t arrive until 2116. 2025 is also a year of rare market conditions that have only been seen a few times in history.

The consensus believes the US economy is entering a new growth phase, driven by mid-cycle momentum, fiscal stimulus, and interest rate cuts – all without reigniting inflation. Moreover, US earnings will likely continue to accelerate while the rest of the world struggles under trade restrictions, a strong dollar, and weak global demand.

Exceptional conditions rarely persist indefinitely, but this broad-based conviction in prolonged US exceptionalism raises questions. Could it be different this time? How long can it last and how can contrarian investors prepare for mean reversion?

US market exceptionalism: how much further can it go?

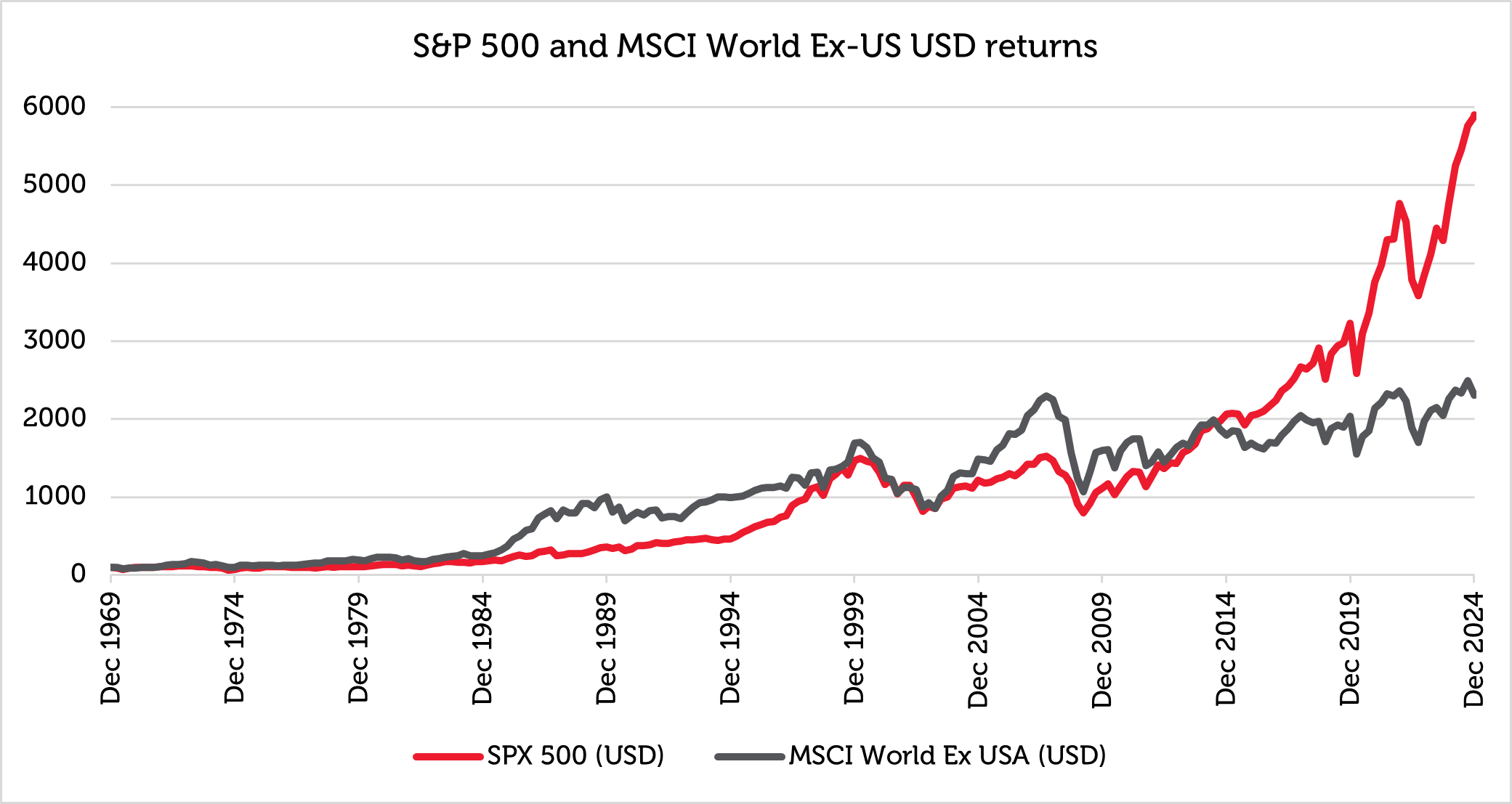

The US has already dominated global markets for more than a decade, with the S&P 500 outperforming the MSCI World (ex-US) by an extraordinary margin.

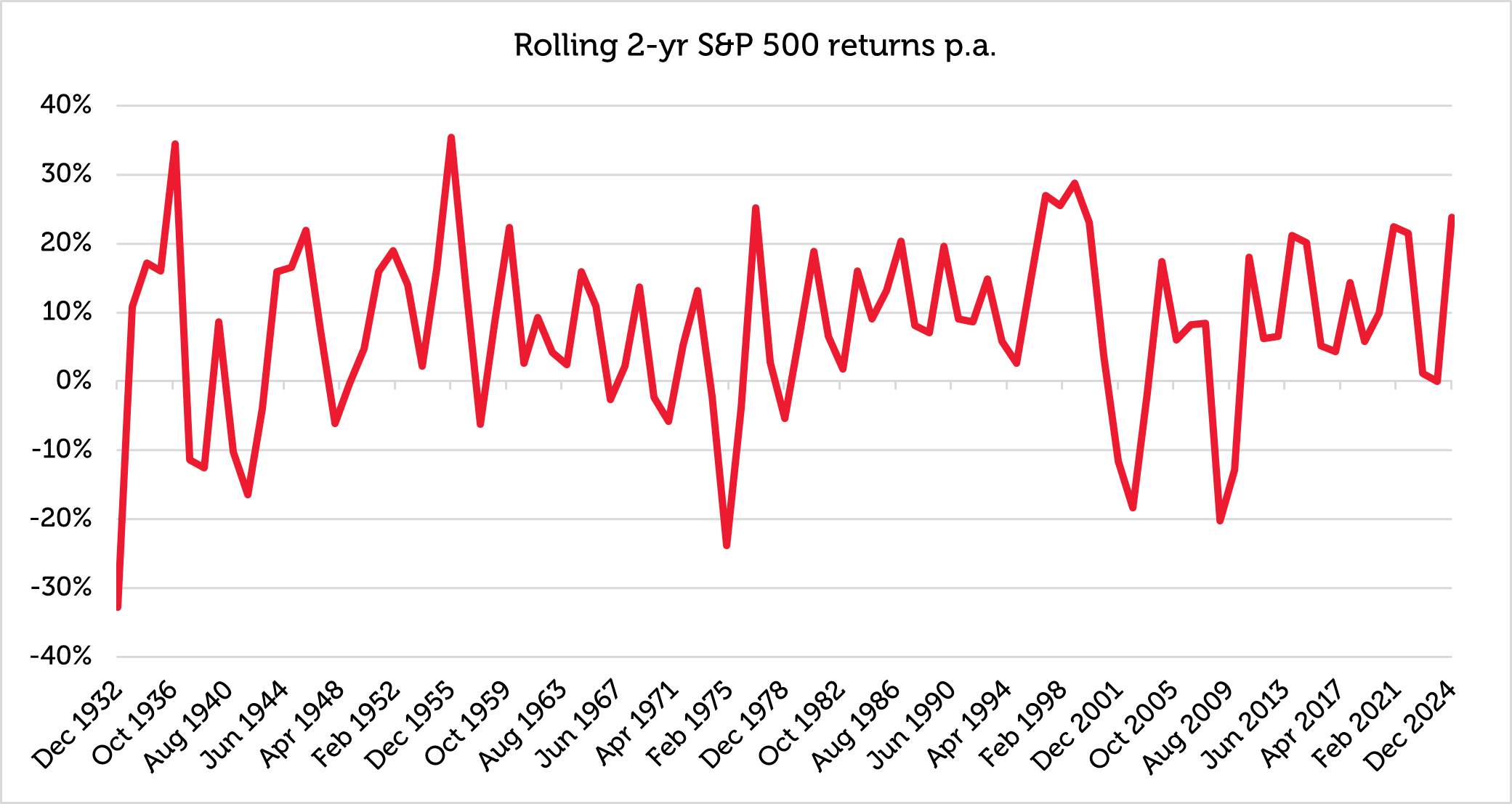

US market dominance reached new extremes in 2024, with the S&P 500 delivering its second consecutive year of 20%+ returns. This is historically rare, occurring only six times since 1929. Even rarer is for the S&P 500 to continue strongly from here. Only in 1995 did the S&P 500 go on to deliver 20%+ return years again. Once in 96 years: rare indeed.

Concentrations are also extreme. US stocks now make up over 75% of the of the MSCI World Index and the top 10 S&P 500 stocks now account for nearly 40% of total market capitalisation[1], comparable only to periods like 1929, the Nifty Fifty bubble of 1973, and the Dotcom boom of 2000.

Today, however, all of these mega-cap stocks are in Technology, specifically AI. Even at the peak of the Dotcom bubble, the market had greater sector diversification.

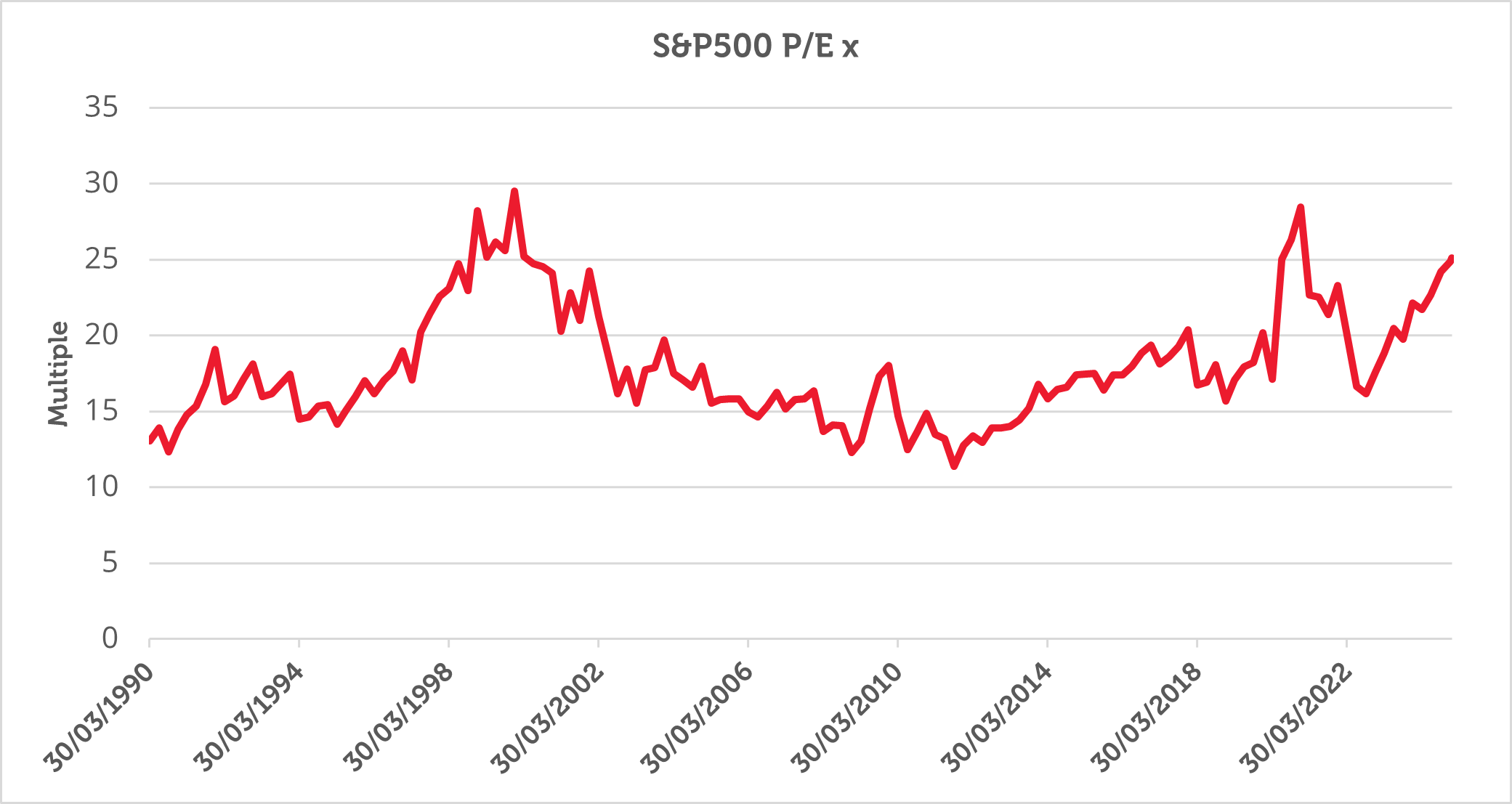

Finally, valuations are also rare. The S&P 500 ended 2024 with a P/E of 25x, a level only seen twice since 1990: the Dotcom bubble and in 2020, when pandemic-driven earnings collapsed. Sustained high valuations have historically been the exception, not the rule – but the market believes that it will be different this time.

1994–1999: A Repeat Performance?

The only time that such exuberance has persisted for any length of time was during the 1994 – 1999 period, a so-called “Goldilocks” period of high growth, low inflation, and falling interest rates.

The US equity market appears to be comparing today’s environment to this period but four crucial differences make a repeat unlikely.

1. Labour market tightness

In the early 1990s, US unemployment was above 7% before gradually falling to 4% by the end of the decade[2]. This provided slack in the labour market, allowing economic growth to accelerate without creating wage-driven inflation.

Today, unemployment is already near historic lows (4%)[3], leaving little room for further declines. To replicate the 1990s’ scenario, unemployment would need to fall to unprecedented levels.

2. Interest rate expectations vs. reality

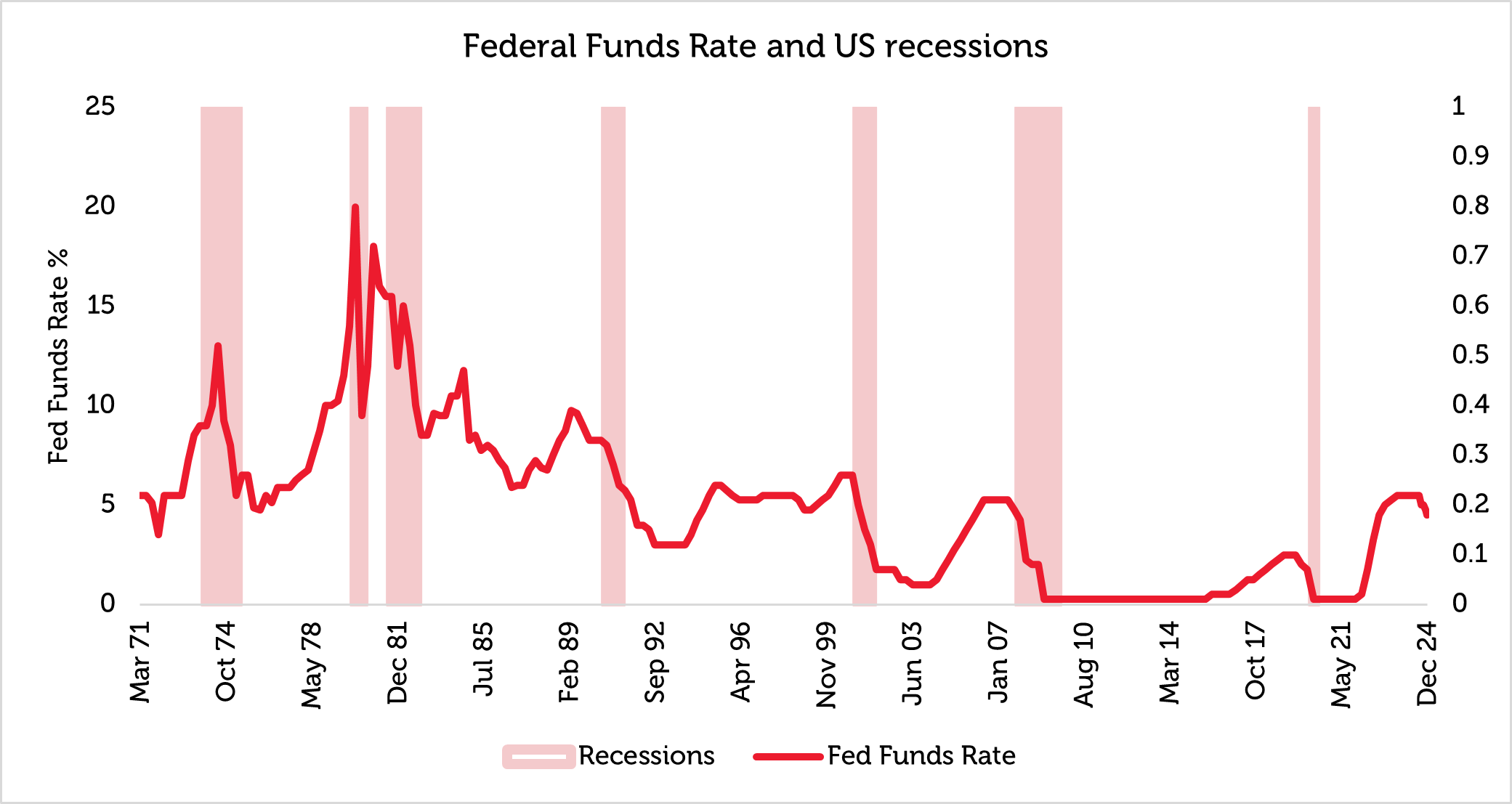

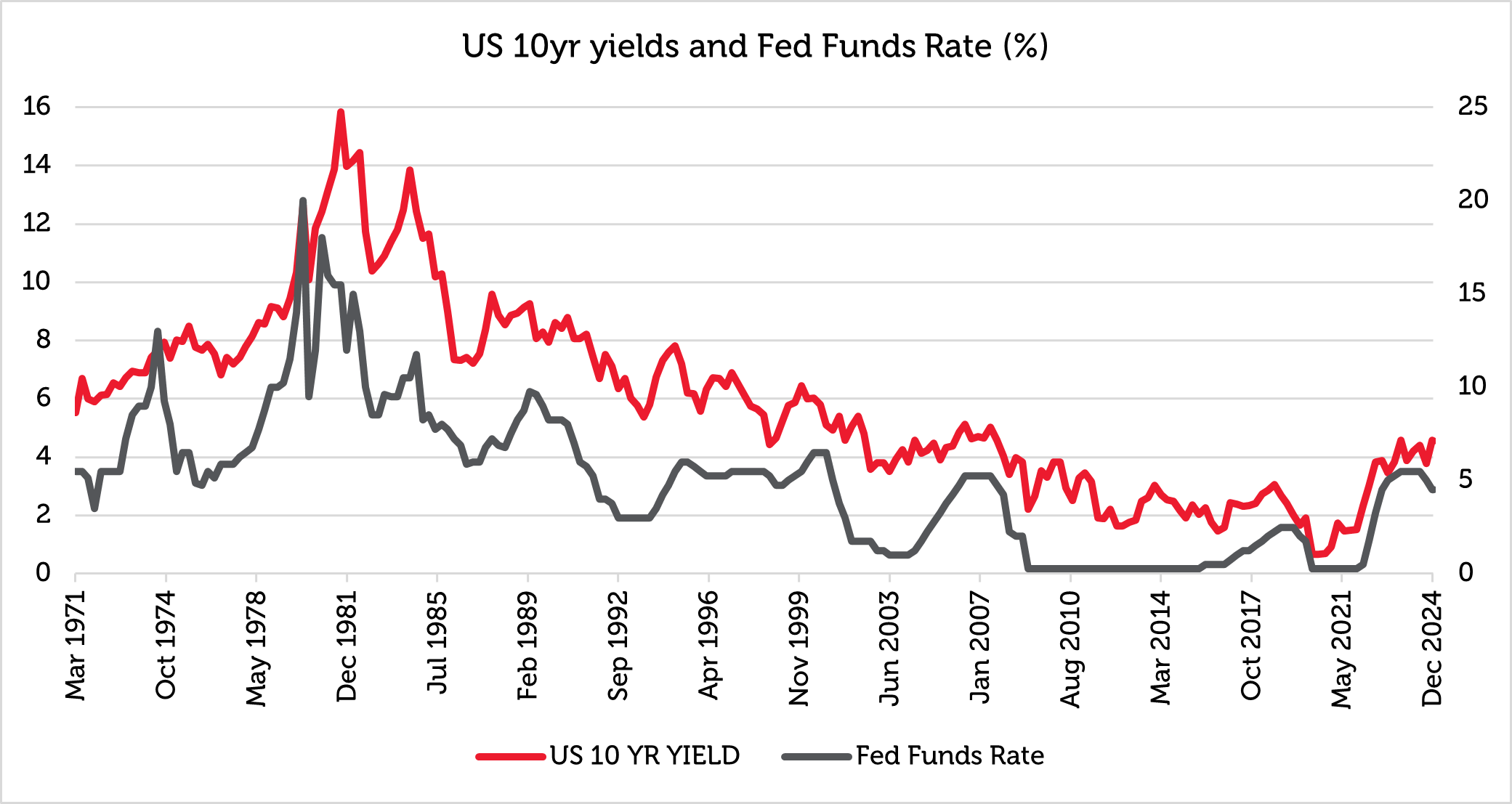

During the mid-1990s, interest rates rose from 3% to around 6% mid-decade, only falling when the Dotcom bubble burst – see the chart below.

Historically, the Federal Reserve has only cut rates meaningfully during recessions, not during expansionary periods. Given that the labour market is already near full employment, meaningful cuts would be rare indeed.

3. Debt, deficits, and fiscal constraints

One of the biggest structural differences between now and the 1990s is the fiscal backdrop.

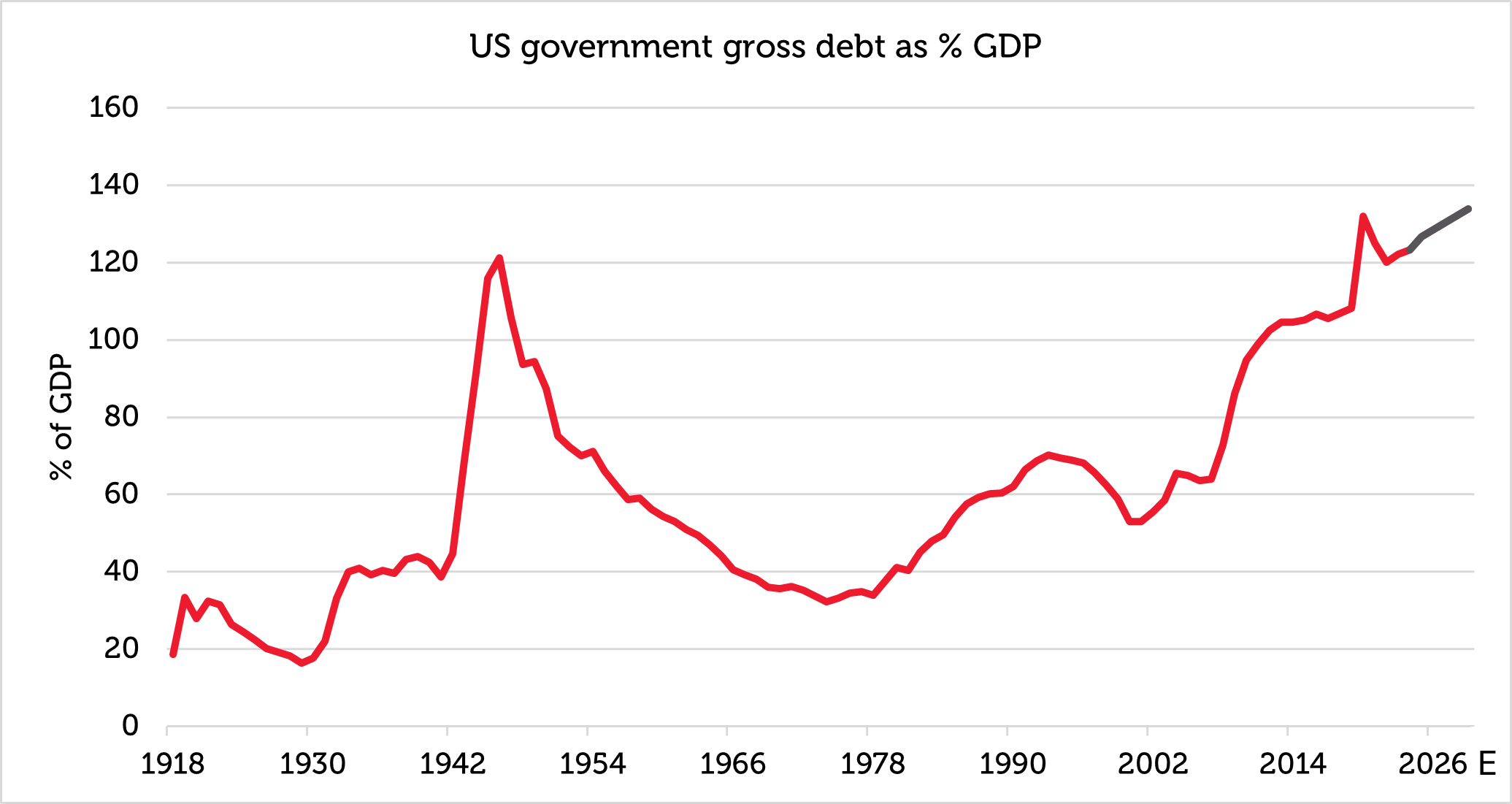

In the mid-1990s, US government debt-to-GDP stood at 70%, leaving room for expansionary fiscal policy. Today, debt-to-GDP is 120%—a level where the US government is significantly more sensitive to interest rate movements.

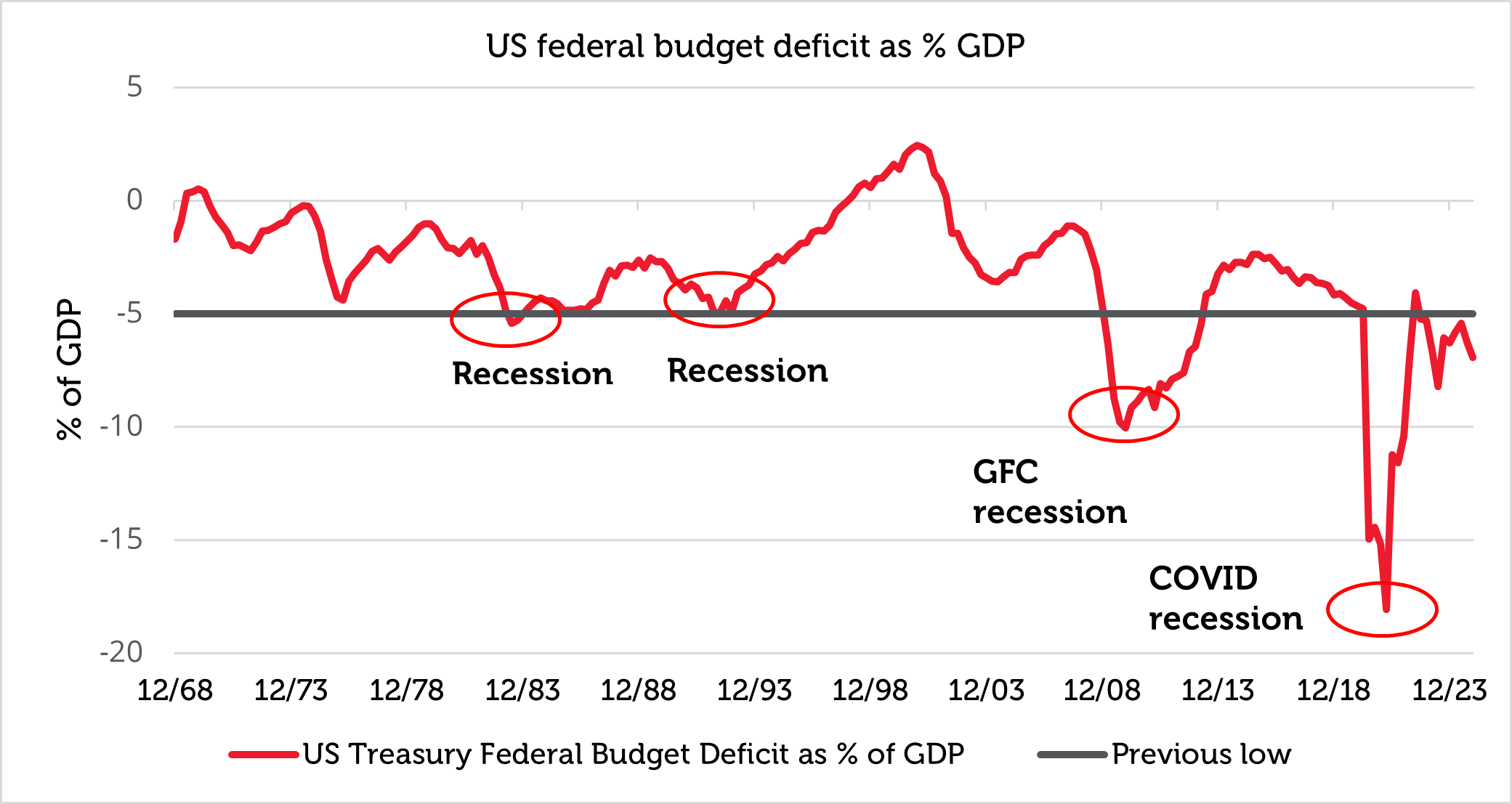

The US deficit is also running at 6% of GDP, a level typically seen during recessions, not economic expansions. With additional tax cuts on the table, fiscal stability is increasingly at risk. Markets appear to assume that deficit spending will have no consequences, but historical precedent suggests otherwise.

4. Inflation risks and bond vigilantism

Consensus remains convinced that inflation will remain constrained, but again, history urges caution.

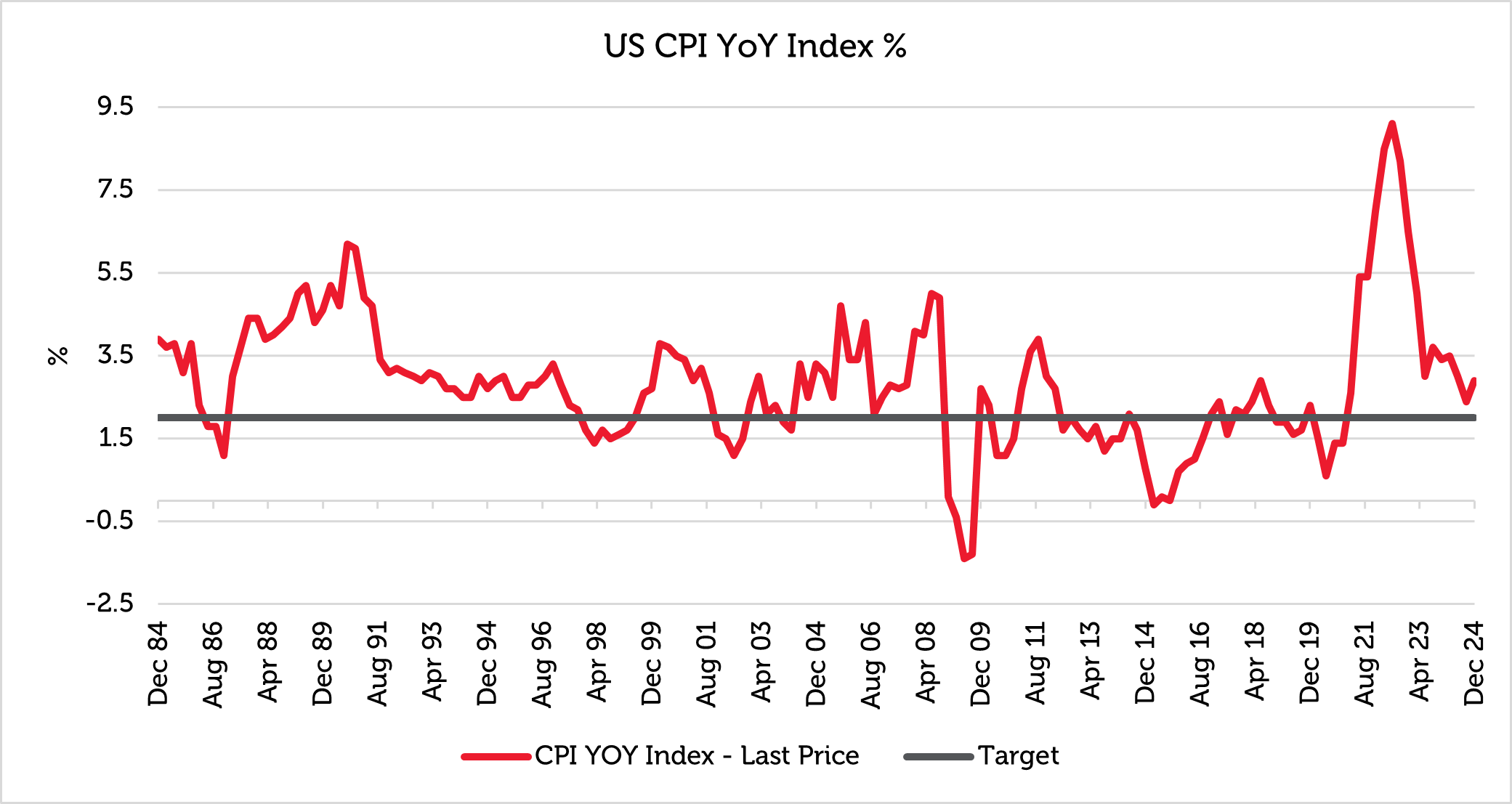

US CPI is currently at c.3%, and significant declines in inflation have historically only occurred in periods of deep economic contraction (e.g., post-GFC). Given tight labour conditions and rising fiscal pressures, it would be rare for inflation to decline from here.

Moreover, debt burdens of this scale have often been eroded by inflation, never by fiscal discipline. Trump’s austerity measures to reduce government spending are unlikely to impact debt levels and the administration could be incentivised to allow inflation to edge higher over time.

Finally, bond markets are signalling concern. The US 10-year yield is rising despite expectations for rate cuts. This last occurred in the 1970s when inflationary concerns ultimately materialised. Equity markets, however, appear to be ignoring these signals.

The case for a disciplined approach to total return investing

At the heart of today’s market optimism is a fragile assumption: US equity markets no longer mean revert. But history shows that excesses—whether in valuation, concentration, or fiscal conditions—eventually correct. Investors in broad equity benchmarks are taking on extraordinary risk, which is why we believe that now is precisely the time to increase allocations to active strategies that offers two key investment characteristics:

1. Rigorous buy / sell disciplines

Strict valuation-based investment disciplines can serve as guardrails to protect against the behavioural biases associated with excessive valuations.

The Redwheel Global Equity Income strategy achieves this by applying an objective yield discipline, ensuring that every stock always compounds at a higher yield than the market. The strategy only purchases stocks yielding at least 25% more than the world index and sells any that yield less than the market.

In addition, a focus on dividend sustainability naturally tilts portfolios toward cash-generative, durable businesses rather than speculative growth stories, ensuring that it avoids crowded trades where market and concentration risk are highest.

2. Maximising total returns

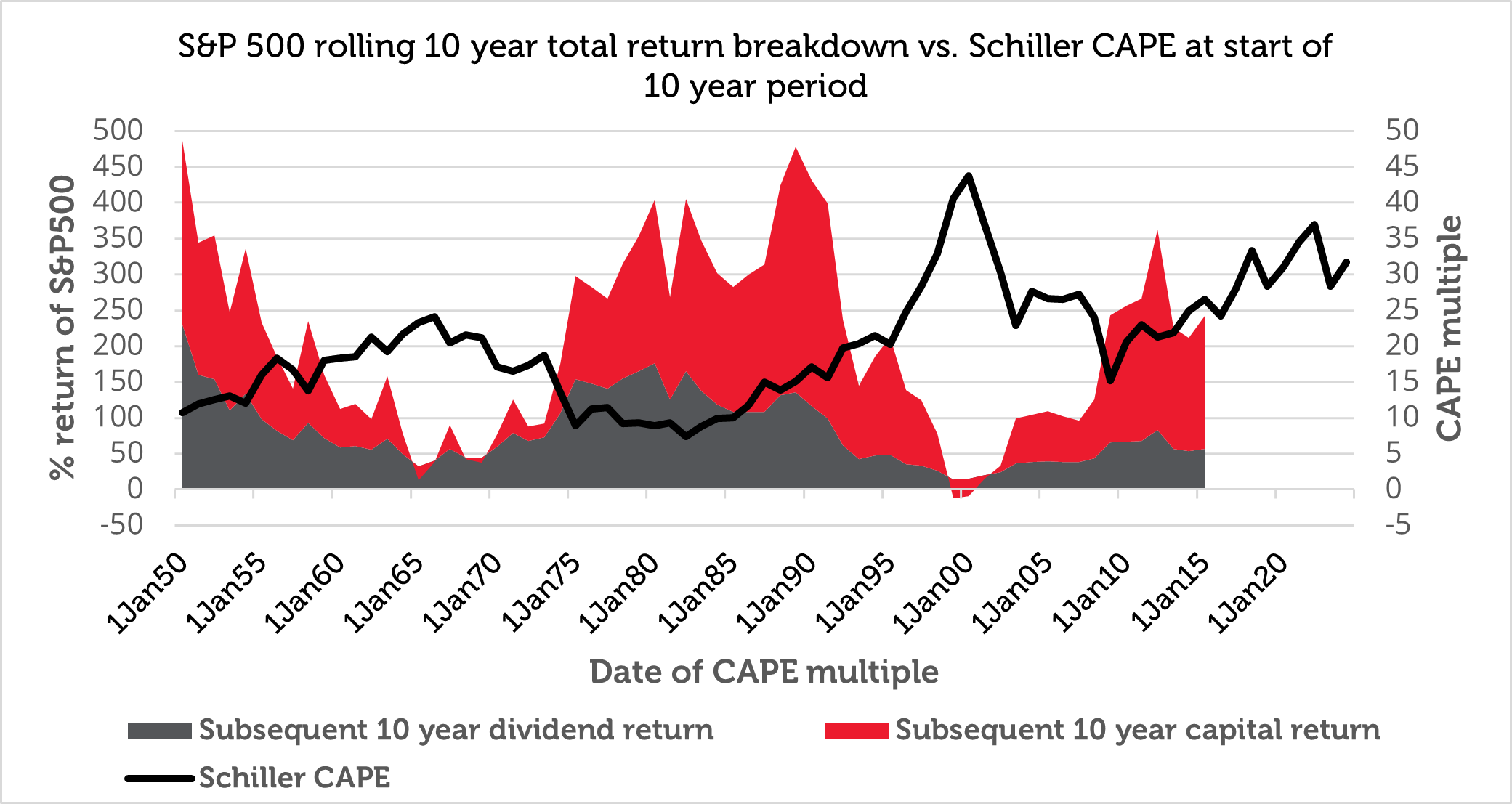

The chart below shows that dividends will likely dominate total returns of the S&P500 over the next ten years.

The composition of the total return over rolling 10-year periods changes meaningfully: sometimes capital return dominates, sometimes the dividend return. Moreover, it tends to correlate with the current valuation[4] at the start of each period. The higher the starting valuation, the greater the probability that the next 10 years’ total return will be driven by the dividend component.

Today’s excessive valuations therefore highlights the value of a quality dividend strategy that compounds a premium dividend yield to the market.

Exceptional conditions rarely persist

Today’s market assumes that growth, high valuations, and AI-driven momentum will continue indefinitely. By contrast, extreme concentration, fiscal risks, and stretched valuations all point to a heightened probability of mean reversion. In such an environment, anchoring portfolios to fundamental principles—quality, yield discipline, and diversification—is not just prudent; it is essential.

A disciplined dividend strategy ensures investors capture the compounding power of income while avoiding the risks of momentum-driven overvaluation. At a time when speculative excess is at its peak, we believe fundamentals provide the best defense against mean reversion when it inevitably arrives.

Sources:

[1] Bloomberg, 31 December 2024

[2] US Bureau of Labor Statistics

[3] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 2025

[4] Shiller CAPE: a widely used cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio which measures how cheap or expensive the market is at any time by dividing the price of the market by the 10-year average inflation-adjusted earnings.

Key Information

No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risks in any market environment. Past performance is not a guide to future results. The prices of investments and income from them may fall as well as rise and an investor’s investment is subject to potential loss, in whole or in part. Forecasts and estimates are based upon subjective assumptions about circumstances and events that may not yet have taken place and may never do so. The statements and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author as of the date of publication, and do not necessarily represent the view of Redwheel. This article does not constitute investment advice and the information shown is for illustrative purposes only.