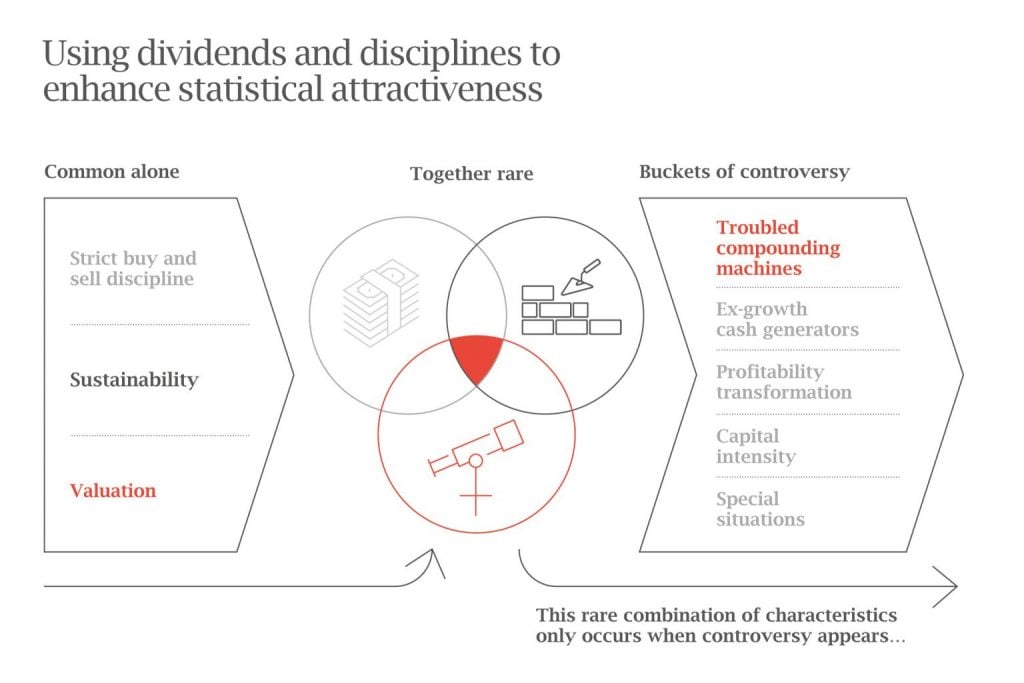

The three requisite features of every investment we make are: a premium yield; dividend sustainability; and a valuation margin of safety. These are relatively easy to find individually but, in combination they are rare and typically only occur when a company is surrounded by some form of risk or controversy.

Here we take a dive into one of the RWC Global Equity Income Strategy’s five buckets of controversy, with the help of three case studies. The Troubled Compounding Machines bucket is often the largest of the five – alongside Ex-Growth Cash Generators, stocks within these two buckets typically make up at least two-thirds of the entire portfolio.

Compounding machines are steady long-term growers that consistently generate high returns on invested capital. As such, their ability to pay dividends is relatively insensitive to changes in operating conditions. They are rarely the fastest growing businesses in the world, but steady growth delivered year after year, tends to result in extremely impressive long-term share price performance and they exhibit all the characteristics required to suffer in difficult times.

Compounders are therefore popular among fund managers, us included. However, this popularity often means a high valuation – some investors would argue that high valuations are justified for these compounding machines and, indeed, that the market doesn’t rate them highly enough. However, even the best companies can disappoint if their valuations become too rich and our dividend discipline means we are protected from such bubbles. We are only able to invest in these quality companies when they are delivering a premium yield.

This discipline means our focus is limited to buying these compounders when they fall under a cloud. Often the trouble will relate to one part of an overall business (divisionally or regionally), but it comes to dominate the consensus view of that stock. In other words, controversy provides us with an opportunity to invest in that business at an attractive valuation, when the share price is already discounting a lot of bad news. If we can get comfortable that the company can recover from the setback, we may be interested in investing.

Case study 1: When PepsiCo lots its fizz

An example of a recent investment (2018) in the Troubled Compounding Machine bucket is PepsiCo. The company is obviously best known for its synonymous fizzy drinks, but it is much more than that these days. It is a stable for dozens of billion-dollar brands, such as Gatorade, Tropicana, Doritos and Walkers Crisps, with entrenched positions in many different country and category combinations.

Nevertheless, at a time when the world is increasingly focused on health and wellness, concerns about the future of the carbonated soft drinks and salty snacks markets have recently weighed on Pepsi’s share price, prompting a more than 20% decline[1].

Refuting the controversy

Rather than being threatened by health and wellness trends, our analysis revealed a business that looked well-placed to cope with evolving consumption preferences. As a dominant leader in the global snacks market, it is in a position of strength in a large and growing industry. Much of the growth is indeed coming in niche categories that are tapping into the growing demand for healthy, sustainable snacking, such as popcorn and vegetable, pulse and bread-based chips. Evidence demonstrates that Pepsi is actually consistently taking additional market share in these categories, albeit from a small base. This reflects some of the key enduring strengths of its business model, including its established distribution network and an agile supply chain.

Pepsi also has a strong number two position in the North American soft drinks market and its Gatorade brand controls three-quarters of sales in the US sports drinks market. Meanwhile, more than a third of group revenues are derived from emerging markets, where growth prospects are even stronger (for example, the average person in China consumes 0.8kg of salty snacks each year, compared to 9.5kg in the US), in an industry where products can be easily adapted to fit local tastes.

Despite the consensus concerns, therefore, we find a business with undimmed growth prospects and a proven ability to successfully use its distribution network to deliver innovative new products to consumers as their behaviour and preferences evolves.

Repeating patterns

We have previously seen a similar pattern emerge in businesses such as the technology business Maxim, where a declining business segment took the focus away from other much stronger parts of the company, and McDonalds, when the headlines focused on the lost relevance of its offering, yet the scale of the business and its embedded distribution network represented key barriers to entry.

As with each of our buckets of controversy, traditional industry boundaries are largely irrelevant. Our familiarity with Troubled Compounding Machines depends upon our understanding of the way these opportunities re-appear in different settings and at different times – the repeating patterns. The characteristics we look for in each bucket are different as are the specific questions we try to answer, because the associated risks can vary a great deal.

In the case of Troubled Compounding Machines, the controversy will likely be relevant to just one part of a much larger business. Nevertheless, the problems will frequently come to dominate the popular market narrative for that stock, even if the troubled division only accounts for a tiny percentage of group revenues. It is therefore vital that we understand how the rest of the business is performing, in order to keep the problems firmly in perspective.

Case study 2: When Qualcomm’s royalty status was challenged

Qualcomm is a technology business that pioneered the development of 3G wireless communication through its innovation in CDMA (Code Division Multiple Access), which is now the dominant form of mobile wireless connectivity. Through this leadership, continued investment in research and development (R&D) and a strong patent portfolio, it has continued to influence standard developments in subsequent generations of wireless telephony.

Despite its long-held market leadership, Qualcomm’s crown started to slip due to a series of legal disputes, centred on the validity of its technology licensing division. Legal challenges were brought simultaneously by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Apple, looking to change the methodology for calculating royalties – indeed, the latter held out on royalty payments for a period from 2017 to 2019.

Refuting the controversy

The stock market tends to find such legal disputes unsettling and that was certainly the case for Qualcomm, whose shares came under pressure, declining by more than 30%[2], as a result of the uncertainty. However, our analysis focused on using past legal precedents to form a positive, evidence-based investment thesis.

Our contentions were aimed at refuting the main accusations against Qualcomm which were that its licensing terms were, in essence, harming competition. By analysing historic disputes, involving the likes of Verizon, Microsoft, Motorola, Samsung and Apple, we found a pattern in which fines were levied but no changes were ultimately required to the licensing agreements. This suggested that the impact on Qualcomm’s share price was disproportionate to the size of the likely settlement and even if one assumed the permanent loss of Apple as a royalty-paying client, the risk-reward characteristics looked skewed asymmetrically in one’s favour.

Meanwhile, we sought expert opinions to support our thesis. Maureen Ohlhausen, who was at the time chair of the FTC, argued for the invalidity of Apple’s legal case, as did Mark Delrahim, head of the antitrust division of the US Department of Justice.

In forming a more positive view of the likely outcome of the legal disputes than the market, we were able to focus our attention on the enduring strengths of Qualcomm’s business model. The company has invested a cumulative $61bn on R&D, which has resulted in a portfolio of tens of thousands of patents, many of which are essential to wireless telephony standards. As these standards (such as 3G, 4G and now 5G) are approved many years before actual products come to market, any company that is able to influence the direction of those standards by evidencing technical superiority and leadership, will enjoy a first mover advantage.

This has long been a feature of Qualcomm’s business model. Every year it reinvests approximately 20% of revenues into R&D, with the aim of maintaining its influence over the direction of the direction of standards for future generations of wireless technology and thereby reinforcing its advantage over competitors. We invested in late 2017.

Repeating patterns

Large, long-held, dominant market positions, enabled by sustained investment in R&D, but eventually threatened by legal disputes and the threat of regulation. We have seen this pattern play out before in the tobacco sector and in the likes of Cisco and Microsoft.

Meanwhile, our scenario analysis will aim to capture the likely downside should the business struggle to solve its problems and assess the upside should they be fixed. Probabilities will be assigned to each of these scenarios, in an effort to arrive at a balanced view of risk and potential reward. Where we find asymmetric risk-reward skewed to future upside, we will look to invest.

Case study 3: When Inditex went out of fashion

Best known in the UK for its Zara brand, Inditex is the world’s largest clothes retailer. A classic compounding machine, the business has delivered exponential growth for more than 20 years, as it has expanded from its Spanish roots into almost 100 countries worldwide. As it has matured, however, the consensus view of the stock has started to reflect a company that is running out of runway for future growth.

A well-documented and once-lauded business model is no longer seen as a barrier to protect its abnormally high returns. A changing competitive landscape, characterised by the rise of online-only fast fashion retailers, has seen its successful business model seemingly emulated – a once-differentiated strategy has become commoditised.

Inditex has successfully expanded online to mitigate some of these challenges, but internet sales are seen to be cannibalising in-store sales, as reflected in the recent decline in gross margins.

Refuting the controversy

In a world where fashions come and go – in the stock market as much as in retail! – one should not be surprised to see the consensus view reflect worries about the enduring relevance of a fashion retailer. The strengths upon which Inditex has been built, however, are more persistent.

In our view, success in apparel retailing is dependent upon, and protected by, the reach and competence of a company’s operational logistics. In this regard, Inditex remains second to none. The scale of its centralised distribution network and the speed of its supply chain combine to provide an important competitive edge. They allow the company to adapt quickly to meet customer demands and make Inditex much less reliant on seasonal sales – Inditex sells 85% of its garments at full ticket price, compared to an industry average of less than 70%.

The rise of the online channel has brought an added layer of complexity to fast fashion operations, but we believe that the future of clothing retail will involve a blend of in-store and internet sales. The ratio of this combination remains unknown, but evidence for it is provided by the recent trend for hitherto online-only brands entering physical stores. We invested in late 2018.

Repeating patterns

Contrary to consensus thinking, we have seen situations before, in which incumbent operators have proven to be better at digitalisation that potential disruptors. Nike, for example, is a leading brand that successfully utilises physical stores as an advertising resource to drive better brand recognition and innovation. Coupled with the reach and availability of a global distribution network, this represents a key barrier, which digital disruptors find hard to emulate.

Meanwhile, within the same industry, Next consistently demonstrates how physical stores can remain a valuable financial asset and an increasingly important part of a successful online platform. Further examples would include RELX and Wolters Kluwer.

Conclusion

Historically, approximately one-third of the Global Equity Income strategy portfolio has been assigned to the Troubled Compounding Machines bucket. Currently, 34% of the portfolio is allocated to the bucket. All three of the case studies detailed above continue to be held within the portfolio, alongside other compelling new ideas such as TSMC and Diageo. This process repeatedly delivers quality at a reasonable yield.

Collectively, we are confident that our track record of identifying and investing in high quality, high return businesses when they have fallen under a cloud, can continue to generate good long-term returns for our investors.

[1] Source: Bloomberg, 29th January 2020. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Portfolio holdings are subject to change at any time without notice. This information should not be construed as a recommendation to purchase or sell any security.

[2] Source: Bloomberg, 29th January 2020. Past performance is not a guide to the future. The price of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Portfolio holdings are subject to change at any time without notice. This information should not be construed as a recommendation to purchase or sell any security.

Unless otherwise stated, all opinions within this document are those of the Global Equity Income team, as at 4th May 2021.